Resonant Voices Radar exposes false, biased or manipulated online content that feeds division and mobilizes support for groups and causes that threaten public safety, human rights, and democracy.

The Resonant Voices Radar’s team monitors the digital ecosystem of open online channels that produce and disseminate misinformation, partisan and extremist propaganda, hate speech, unsubstantiated claims, and other dangerous online messages that spread across borders, languages, and platforms, affecting transnational diaspora communities.

In April 2020, the Resonant Voices Radar analysed the resonance and reach of the following stories:

Bleiburg: A Symbol of Divisions Even Beyond the Balkans

Whenever Bleiburg is mentioned, people in the Balkans begin loading their weapons with lead in order to take part in social media warfare over the “real” historical truth. Over the past decades, the small Austrian town on the border with Croatia, whose name literally means “lead fort”, has become a symbol of an online warfare, in which deceptive statements, hate speech and extremist attitudes are used for the purposes of historical revisionism, ideological warfare and the relativization of crimes.

This year’s decision of Catholic Bishop Vinko Puljić to hold a religious commemoration for the victims of the “Bleiburg tragedy” and the “Croatian Way of the Cross” in Sarajevo provoked an eruption of online and offline reactions. Inflammatory narratives spilled from the online environment onto the streets and vice versa, creating new, and strengthening old lines of ideological, interethnic and inner-Croatian division.

The controversial mass was dedicated to the 75th anniversary of the revenge killings of several tens of thousands of members of the pro-Nazi Croatian Ustasha regime and army, members of German Nazi troops, Muslim pro-Nazi groups, Serbian and Montenegrin Chetnik groups, White Guard anti-communist troops, Slovenian Quisling troops, but also of civilians. These killings, committed at the end of the Second World War near Bleiburg, were carried out by members of the Yugoslav People’s Liberation Army.

In the past decades, Ustasha uniforms, the call “Ready for the homeland” and the checkerboard symbol with the first field in white, used during the pro-Nazi Independent State of Croatia (Nezavisna Država Hrvatska, NDH), have come to represent a recognisable part of the commemorations in Bleiburg, which is why this gathering is viewed as part of the attempt of historical revision, the glorification of the fascist Ustasha regime and the relativisation of its crimes in the Second World War.

The announcement of a similar mass in Sarajevo provoked violent reactions among social media users, and inspired an anti-fascist protest march through the streets of Sarajevo during the controversial mass.

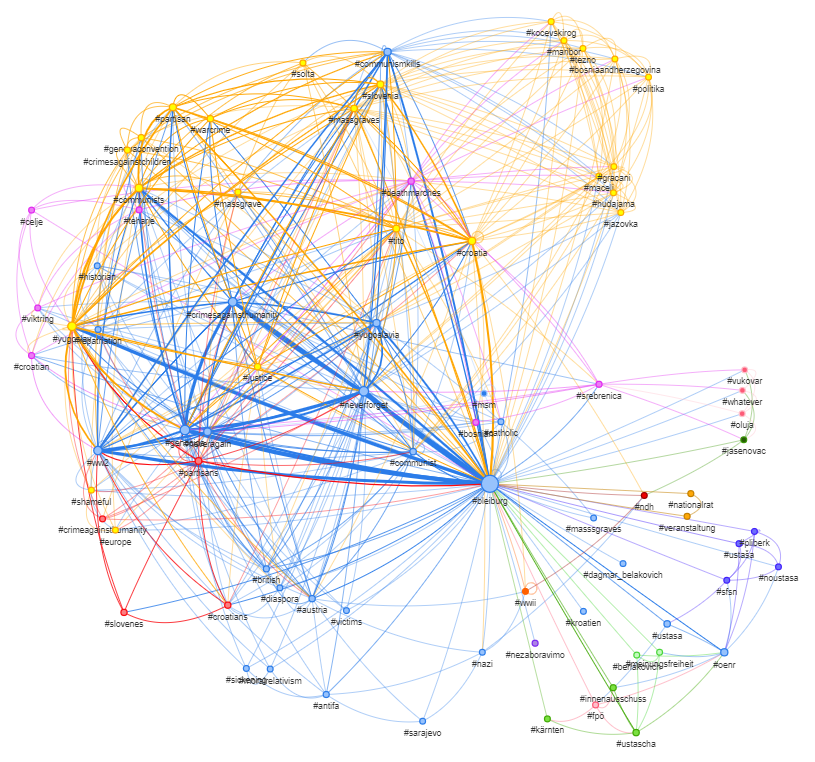

During June, the fight between the two sides continued online. An analysis, conducted with the application SocioViz, indicates that Bleiburg is a topic that dominantly divides Twitter users along two lines. One line of division is into anti-fascists vs. Ustasha, and the other is into communists/Yugoslavs vs. nationalists/Croats.

The network of hashtags used in the most influential tweets related to Bleiburg, indicates that at the beginning of June, the prevailing narrative on Twitter was one that viewed Bleiburg exclusively as a war crime committed by Yugoslav communists. The graphic is dominated by the blue and yellow networks of hashtags that directly link communists, Yugoslavia and the partisans to the mass graves and killings in the places of Jazovka, Gračani, as well as the expulsion of dissidents to the island of Goli Otok.

Following this is the pink network, which connects this narrative with the genocide in Srebrenica, but not Jasenovac. Visibly smaller and separate, are the purple and the light green networks of hashtags, which pointed out the crimes of the Ustasha regime, as well as the opposition to the commemoration in Sarajevo.

Even though the activity of these users was significantly higher in May, around the time of the controversial commemoration, it died down at the beginning of June.

Contrary to that, the activity of the representatives of the opposing narrative did not die down, and the analysis of the impact of individual Twitter accounts indicates that the most active account was the one dedicated to the “revealing of the truth about the genocide against Croats and others committed by the Yugoslav dictator Tito and his communists”.

Analysing the digital content provoked by the Bleiburg commemoration in Sarajevo, the RVR team managed to identify five dominant points of manipulation used for the sake of maintaining the aforementioned lines of division.

In the social media posts, but also in texts, both in mainstream and in alternative media, the dominant points of manipulation are mostly related to the number of those that have perished around Bleiburg, their identities, the anti-fascist movement, communist rule and the link to crimes in the region.

The number of those that perished: Historians mostly agree that the number of those that perished is between 45,000 and 60,000. But in the controversial online posts, this number is significantly inflated, somewhere between 300,000 and 600,000, while some quote the claim of one Croatian portal that fuels historical revisionism, which states that “more than a million people were displaced, killed or expelled from Croatia” at the time of Bleiburg.

The identity of those that perished: In the posts, it is often pointed out that “members of the Croatian army and numerous refugees” perished near Bleiburg, which is not incorrect, but it represents tendentiously placed half-truth. By frequently omitting the fact that it was members of the NDH troops, many of which had committed crimes, the attempt is made to distort the context and to strengthen the narrative of “innocent victims”. By omitting the historical fact that members of Slovenian, Serbian, Montenegrin and Muslim fascist formations were also retreating towards Bleiburg with the Croatian Ustasha, the attempt is made to maintain the myth of an exclusively Croatian suffering of losses.

The anti-fascist movement: The omission of the national identity of all those killed in Bleiburg fuels another controversial narrative – an endeavour to exclusively link the Yugoslav anti-fascist movement with a supranational Yugoslav idea and with communism. In this narrative, the anti-fascist struggle is presented as a fight against the Croatian people, purposefully ignoring the role of around 140,000 ethnic Croats who were members of the anti-fascist movement and the Yugoslav People’s Liberation Army.

Communist rule: On both sides of this ideological conflict,the role of communism and of president Josip Broz Tito are viewed in a distorted mirror. In the online posts of those close to Croatian nationalist circles, especially in the diaspora, every mention of Yugoslav communism is coloured by claims about the political persecution of Croats, the suppression of Croatian statehood and communist crimes against Croats. On the other side of the dividing line, every question about how Tito’s communist regime treated political dissidents is considered as a blow against the anti-fascist tradition and the idea of a multinational state.

Linking to crimes: The faultline between Yugoslav anti-fascist identity, on one side, and Croatian nationalist one, on the other, also frequently manifests itself in the references to “our” and “their” crimes. The social media posts that mention Ustasha crimes provoke mentions of Bleiburg, but also of Goli Otok, where Tito’s regime imprisoned political prisoners. The “war of crimes” continues by mentioning Serb, Jewish and Roma victims in the Ustaha camp of Jasenovac, then turning to infamous places of suffering in the wars of the 1990s, from Vukovar, the military-police action Oluja, to Srebrenica.

The synergistic effect of these 5 types of manipulation is such that historical revisionism and relativisation are achieved by putting them in the context of an ideological war between anti-fascism/globalisation and nationalism/populism. This forms the context of a conflict that is also carried out way beyond the borders and the context of the Balkans.

In this fight, the roles of the liberators and the criminals get mixed up, and so a segment of the public gradually loses the feeling for who the positive one is, who the negative one is, or who the defeated one is and who the winner is, in a certain historical moment.

In May and early June, the discussion around the Bleiburg commemoration spilled from social media into real life and vice versa. In this dynamic process, a quite unexpected heroine from the offline environment emerged in the online environment.

As it was first reported by eyewitnesses on social media and then also in mainstream media, an elderly lady managed to interrupt a pre-election rally of right-wing parties in Dugo Selo near Zagreb. As they stated, she was annoyed by the Ustasha iconography displayed at the rally, so she came out of her house in her slippers and with curlers in her hair in order to prevent this gathering.

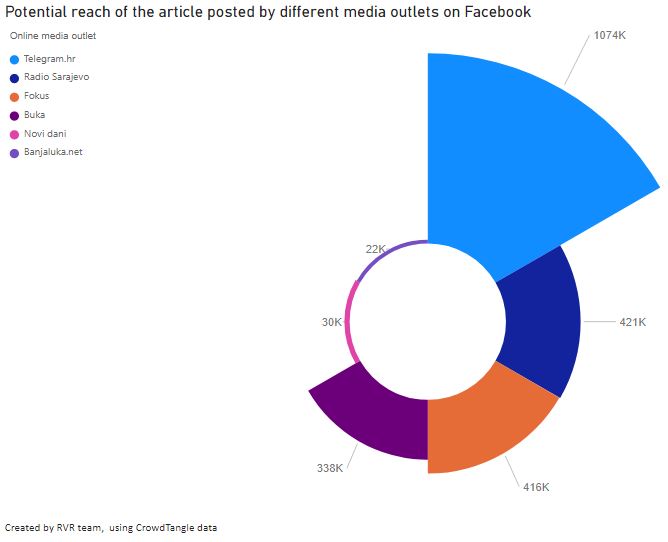

She soon became a hit on social media. Media in Croatia and in Bosnia and Herzegovina reacted promptly by publishing the story on their portals generating millions of visits. Just one of them, the Croatian outlet Telegram, reached almost 1.1 million Facebook users with this story.

Almost identical articles were published on at least five media portals in the region, contributing to the potential Facebook reach of these six articles of 2.3 million in total.[1]

The heroine of this story was inevitably also classified according to the dichotomy of anti-fascists vs. Ustasha and communists vs. nationalists. For parts of the audience she is a heroine. For others she is a “skojevka”, which once signified a female member of the League of the Communist Youth of Yugoslavia (Savez komunističke omladine Jugoslavije, SKOJ), and which is now mostly used as an insult by nationalist commentators.

Anti-immigrant rhetoric sometimes brings more clicks than votes

During the past five years, anti-immigrant narratives brought votes to many political parties and movements in Europe, even helping some of them into power. But the results of the June parliamentary elections in Serbia show that success in spreading such messages in the digital world doesn’t always translate into votes in the ballot box.

A video of an attack on a migrant centre on the outskirts of Belgrade was not just massively shared on social media, but it was also used as a trigger for the beginning of an election campaign. The video shows a far-right activist driving his car into a migrant centre in an attempt to run over some of the residents there.

With clear reference to the Christchurch terrorist attack in New Zealand, the attacker live-streamed his action on Facebook, which was accompanied by hate speech against migrants. Fortunately, no one was injured in the attack and the attacker was arrested.

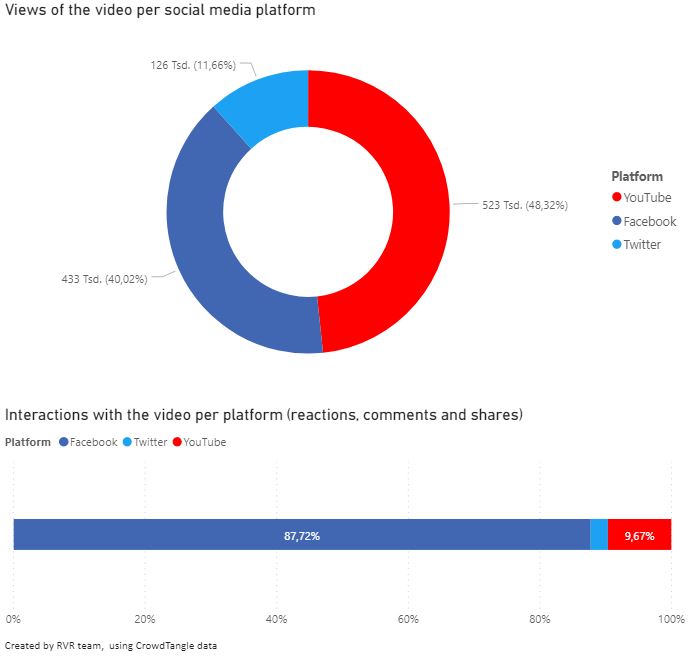

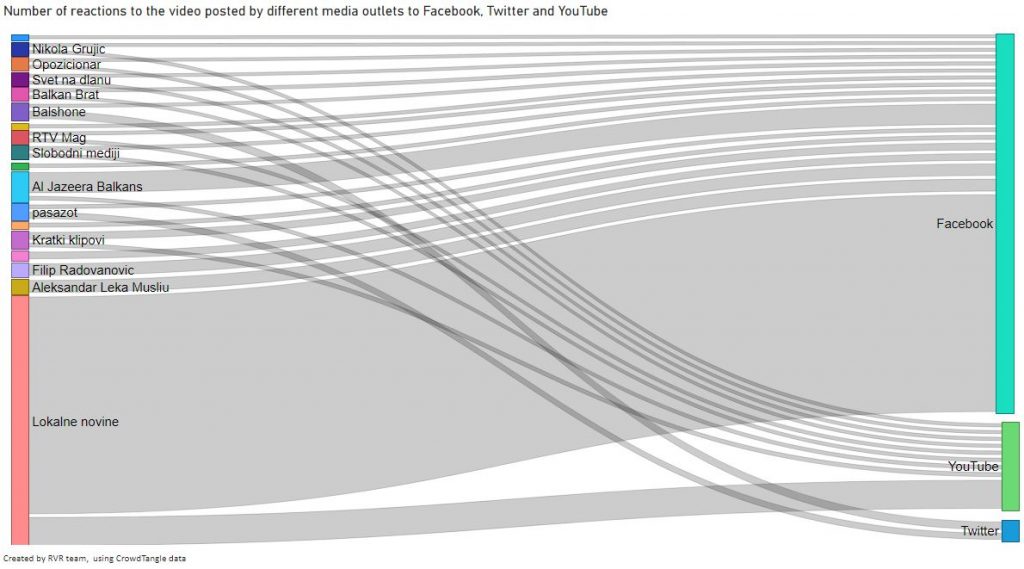

So far, the attacker’s live-stream video on Facebook has been viewed around 56.500 times, but its reach was much higher. In total, the RVR team registered 20 uploaded videos of the attack on three dominant social media platforms – Facebook, Twitter and YouTube – and in total, they generated more than 1.08 million views.

The Facebook live stream video of the attacker is still on his Facebook profile, which is still active. None of the platforms have removed or flagged the video as inappropriate content. The posts by social media users, which used the publication of the video to spread hate speech and to incite violence against migrants in Serbia, have not been flagged as inappropriate content either.

The videos that were directly uploaded on YouTube had a few more views than the videos uploaded on Facebook, but Facebook had more than 85 per cent of the total number of user interactions from all three social media platforms.

Two organisations, known for their anti-immigrant views, tried to use the influence of the video: the “Živim za Srbiju” (“I live for Serbia”) movement founded predominantly on an anti-vaccination and a nationalist platform, and the far-right Levijatan (Leviathan) movement, which presents itself as an animal protection organisation.

Levijatan’s leader, Pavle Bihali, openly supported the attack on his Twitter profile and provoked thousands of reactions, not just on social media, but also in nationalist media. Similar support came from Dr Jovana Stojković, leader of the “Živim za Srbiju” movement. They both called for a joint protest in front of the migrant centre where the attack had happened.

Both organisations used the protest as the beginning of a joint election campaign in which they tried to broaden the reach of their messages, using mainstream media appearances in combination with social media activities.

Through their activity on online platforms, such as posting videos of Leviathan members “patrolling their neighbourhood, keeping locals safe and painting over symbols written by non-European migrants”, this group managed to gain the support of nationalists even outside the region. On Twitter, they received direct support from one of the most influential Polish nationalist Twitter users.

However, the teaming up of the two movements, which are very active and forceful in the online environment, did not produce a synergistic effect in offline election activities. The electoral list of these two movements gained less than 22.700 votes, even though the Leviathan movement alone has 11 times more Facebook followers.

One of last year’s Resonant Voices scholarship awardees, Michael Coulbourne, wrote an in-depth analysis about the Leviathan movement for the website Bellingcat, it can be found under the following link: https://www.bellingcat.com/news/2020/06/18/levijatan-serbian-animal-rights-vigilantes-go-to-the-polls/

Bizarre stories about migrants spread faster if the government is blamed

In May, the small Serbian border town of Šid became prevalent in anti-immigrant posts of social media users in the region. Serbia’s president Aleksandar Vučić sent members of the military to help the police in securing migrant and asylum centres in and around Šid, where migrants frequently try to cross the Croatian border to reach the European Union.

Serbia’s president pointed out that, after the reopening of migrant camps, which were completely closed during the two-month state of emergency introduced due the COVID-pandemic, there is petty theft and unauthorised intrusions onto property, which is why citizens don’t feel safe.

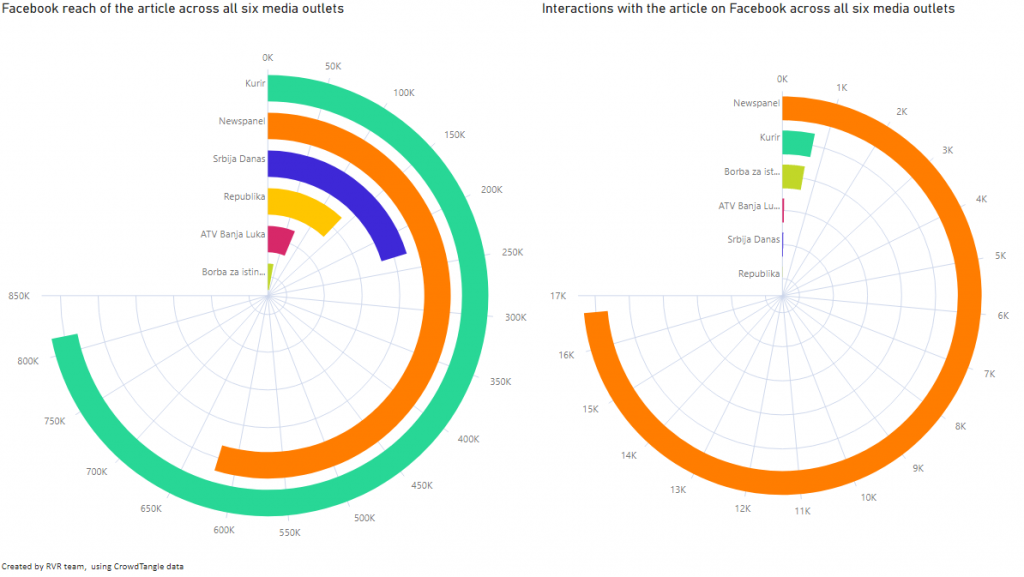

Despite the government’s effort to convince the population that Šid is safe by having the military present there, unsubstantiated claims made by just one tabloid had so big echo-chamber effect that it had a potential reach of more than 1.5 million people on Facebook alone. Moreover, the number of reader interactions increased tenfold as soon as the whole anti-immigrant narrative was put in the context of criticism of the Serbian government.

The RVR team analysed the reach of a text by the tabloid Srpski telegraf, published on its portal Republika, which reported, without any adequate journalistic check-up, the interlocutor’s claim that migrants had killed his two dogs. This bizarre story, full of outrageous details of the killing, was published as fact despite there being details in the very text that indicated that the credibility of the source was disputable. As was reported, the interlocutor chopped down 300 fruit trees so as not to leave them to the migrants, and hung a dead owl and put up the head of an ox to dissuade the migrants from entering his property.

This insufficiently verified and biased content was quickly spread on the portals of nearly all tabloids in Serbia, but also on some alternative media portals, where it was put in a slightly different context. The same content was re-contextualised as criticism of the “pro-migrant politics” of Serbia’s president, pointing out that the alleged perpetrators were “Vučić’s migrants”.

Even though Newspanel is a little-known alternative media portal, its article was shared on Facebook by numerous far-right, nationalist, pro-Russian and anti-immigrant groups across the region and the diaspora, which gave it a potential reach of 620,000 people.

The same portal had the highest reader engagement rate in relation to the number of its subscribers on Facebook. It had an engagement rate of 2.69 per cent, while well-known tabloid newspaper Kurir was able to get only 0.1 per cent of its followers to engage with the article in terms of shares, likes and comments.

On the other side, a little-known portal Borba za istinu achieved an engagement rate of almost two per cent among its subscribers on Facebook who obviously seem to be more prone to engage with the article compared to the other outlets’ subscribers.

The analysis of this case indicates that, when an anti-immigrant narrative is combined with the criticism of the government of president Vučić, as a consequence, it has an incomparably higher reader interaction than similar texts without the anti-government context. The proportions of the increase of reactions are so large that just one text with an anti-government context actually generates 92 per cent of the total number of reactions, comments and shares generated on Facebook by all six analysed texts of very similar content.[2]

Never-Ending Stories

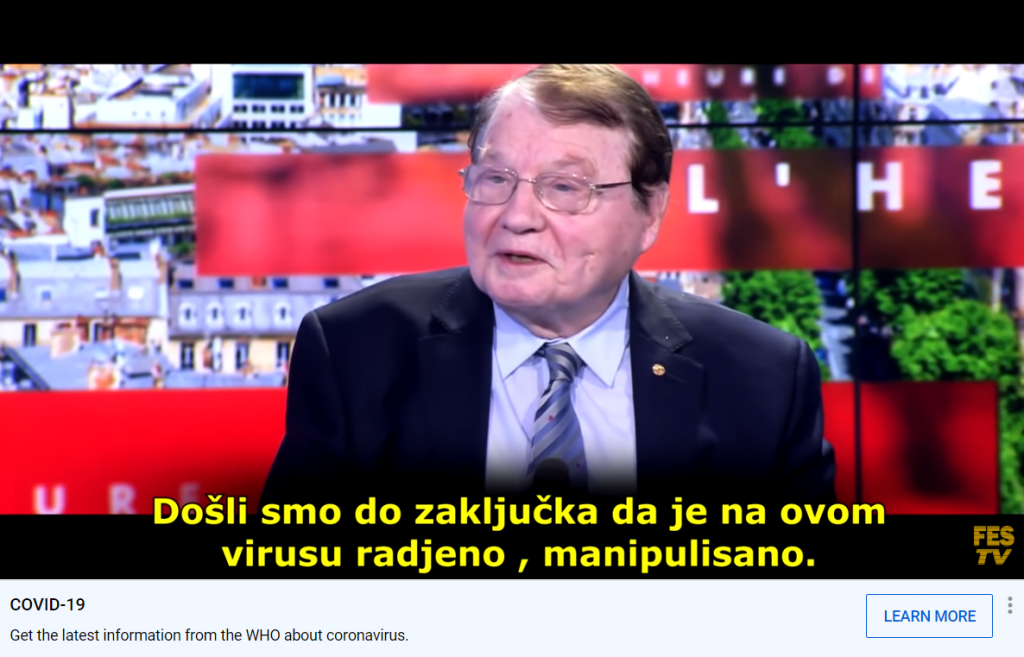

The coronavirus pandemic dominated April’s Resonant Voices Radar, which identified four doctors whose statements were especially influential among online communities in the EU and the Western Balkans. Trends in the Internet searches of users in all communities of the Western Balkans indicate that the interest in them continued throughout May.

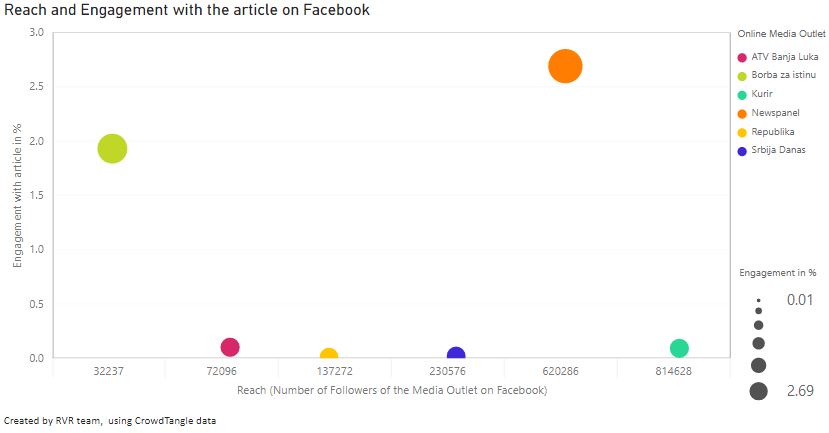

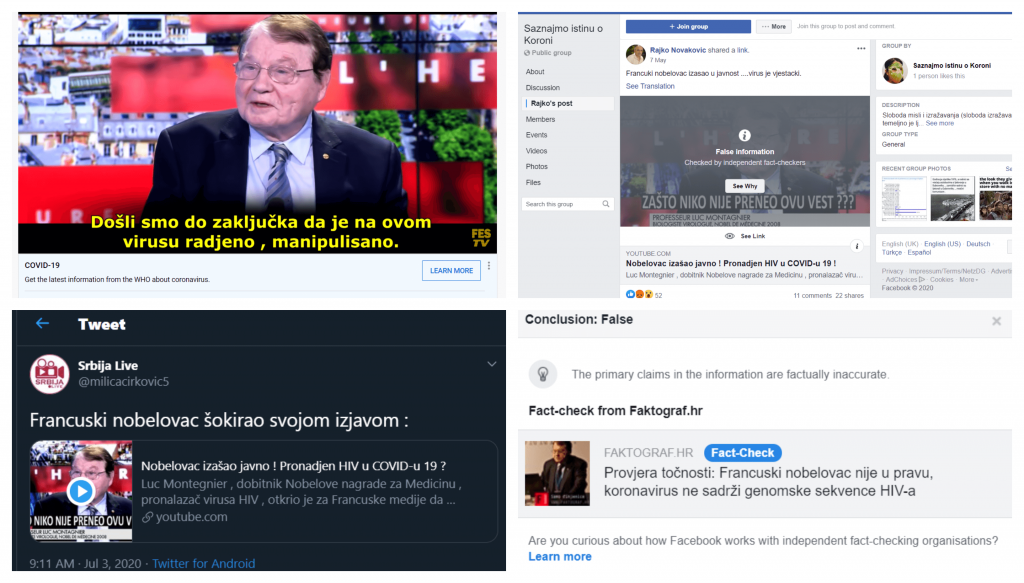

In May also, language barriers did not prevent the spread of unsubstantiated claims of Western doctors among the audiences in the Western Balkans. A huge penetration within the online community had a video of a TV interview in which French virologist and Nobel Laureate Luc Montagnier claimed, contrary to the majority of the scientific community, that the coronavirus was made artificially and that it contained elements of HIV.

Just one YouTube video with a translation into the local language was watched by nearly 550,000 people. On Facebook, it was watched by nearly 630,000 users, generating around 48,000 reactions, mostly within groups and pages which propagate nationalist views, conspiracy theories, opposition to vaccination, but also among the Balkan diaspora in France and Austria.

Platforms reacted differently to the spreading of this video among social media users. YouTube added a uniform link to the World Health Organisation’s latest information about Covid-19 underneath the video, while Facebook obscured the video and marked it as false information, referring to the Croatian fact-checking portal Faktograf.hr. Twitter did not mark or check posts with this video.

[1] Six articles generated more than 13,300 reactions, comments and shares on Facebook.

[2] Even though the article published by the tabloid Kurir individually had the biggest reach among the six analysed texts, that were the same or similar, the text of the portal Newspanel, that linked the anti-immigrant narrative with the anti-government narrative, generated many times more interactions of Facebook users. The Newspanel text generated more than 16,000 reactions, comments and shares on Facebook, while the texts of the other five portals in total generated less than 1,500.

The Resonant Voices Initiative in the EU is funded by the European Union’s Internal Security Fund – Police.

The content of this report represents the views of the Resonant Voices Initiative’s media monitoring team and is the sole responsibility of the Resonant Voices Initiative. The European Commission does not accept any responsibility for use that may be made of the information it contains.