A survey of young Serbs living abroad provides a snapshot of a more open-minded community ready to acknowledge and condemn Serbian responsibility for war crimes committed during Yugoslavia’s collapse. But even they are not immune to enduring narratives of victimhood and manipulation of the 1995 Srebrenica massacre.

By Katarina Tadic

Nebojsa is a 30-year-old Serb with a postgraduate degree and a job with a London public relations firm. On a sunny day in May, he was wearing a suit and sipping an espresso at Pret a Manger, barely distinguishable from his fellow London professionals.

Originally from Belgrade, Nebojsa [not his real name] says he actively follows political developments in his native Serbia, often via the mobile phone app of the regional broadcaster N1, an affiliate of CNN and whose questioning of the official government narrative in Serbia has made it a thorn in the side of the country’s powerful president, former ultranationalist Aleksandar Vucic.

Vucic’s ruling Progressive Party and its allies in government have drawn criticism in recent years from rights groups for their readiness to engage with – on occasion recruit – former Serbian officials or military officers convicted of war crimes during the collapse of socialist Yugoslavia and released having served their sentences.

“Those people are free, but they are not free from the moral responsibility they had during the war,” Nebojsa said, adopting the critical tone common among young, well-educated and so-called ‘Westernised’ Serbs towards Serb war crimes during the final decade of the 20th century.

Yet asked about Srebrenica, the Bosnian enclave where some 8,000 Muslim men and boys were killed by Serb forces in 1995, Nebojsa is equally adamant in rejecting UN-court findings that it constituted genocide. “I don’t think it was genocide,” he said.

For many Serbs in Western Europe, the two statements are not mutually exclusive, but in fact reflect a conflict prevalent among a section of Balkan diaspora communities – those who left the region over the past decade with solid grades and career prospects, not fleeing war but seeking well-paid opportunity.

If for years it was assumed that Balkan diaspora communities – which grew with the bloody collapse of federal Yugoslavia – exercised a “long-distance nationalism”, nurturing simplified narratives of their country’s demise and the responsibility of others for the bloodshed it unleashed, young professionals like Nebojsa, who have few direct memories of the wars themselves, are viewed as more open-minded.

A BIRN survey and in-depth interviews, however, suggest that while those like Nebojsa show a willingness to acknowledge and accept Serbian responsibility for war crimes – and the need for reconciliation – they are ready too to embrace parts of the nationalistic narrative still prevalent within Serbia itself two decades after the wars ended.

‘Views held by this wave of migrants are more open’

Reconciliation is a long-term process with the primary goal of finding the means to address a painful, sometimes violent past and create condition for peoples to live together with a shared positive vision of their common future.

Srdjan Hercigonja, a political scientist and project manager at the German forumZFD in Belgrade, defines reconciliation as “a set of political, social, economic and cultural activities among the once warring parties that would contribute to the transformation of conflict in the former Yugoslavia.”

A key element of reconciliation is establishing the truth of what went on and holding to account those responsible for war crimes.

The diaspora role in reconciliation is considered significant given it can contribute to and foster structures and initiatives that promote peaceful co-existence and the means to deal with the past in home countries.[1]Given the lack of a common definition, for the purposes here, diaspora is considered to be “individuals with distinct links (ethnic, social, cultural, economic) to a country of heritage other than their country of residence”.

Some authors argue that such engagement can alleviate tensions in the diaspora community itself, particularly within “conflict-generated diaspora”.

For the Western Balkan region, for years it was assumed that the diaspora was the last bastion of nationalism.

“Typically, diaspora cultivates the myth of the triumphant return,” Adriano Remmidi, a human rights expert at the Global Campus for Human Rights, a Venice-based, European Union-funded network of universities, told BIRN. Away from their homeland, the diaspora nurtures “long-distance nationalism” – a static view of the native country and a simplified (re)interpretation of the Yugoslav wars.

Hence, reconciliation efforts in the former Yugoslavia typically did not include diaspora but focused exclusively on those who stayed behind.

In the meantime, however, the reasons for and forms of migration have changed, as has the profile of migrants.

Tena Prelec, research associate at the London School of Economics, explored Serbian diaspora political views on the country’s 2017 presidential election, writing that today, when talking about the diaspora, one must bear in mind that, “The views held by this wave of migrants are more open, concerned with problems of governance rather than with topics linked to national pride, and critical of the current direction of travel of their home country.”

Bearing in mind the rate of emigration among young Serbs, such findings suggest a greater potential role for them in the processes of reconciliation. Their constructive engagement could contribute to democratisation and consolidation of the rule of law, aiding in turn efforts to encourage Serbia to deal with its past.

Diaspora not immune to prevailing Serbian narratives

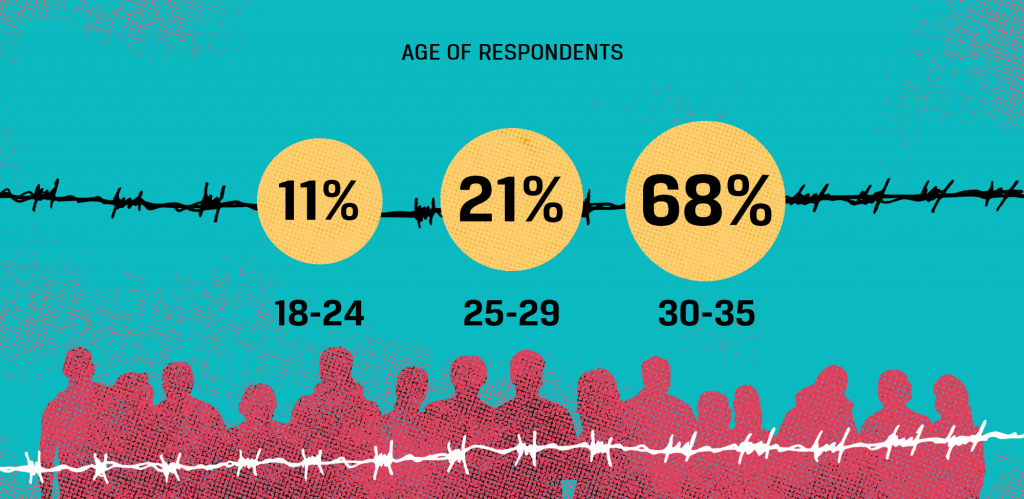

In May and June 2019, BIRN conducted a small quantitative survey among young Serbians aged between 18 and 35 and living in the EU. There were 130 respondents.

The survey was distributed via email with the help of diaspora associations as well as on Twitter and Facebook.

The questionnaire contained closed-ended questions and focused on Serbian responsibility and accountability for crimes committed during the Yugoslav wars.

Half of the respondents were men, half women. The majority were aged 30 to 35, meaning they have limited direct memory of the period in question.

More than 80 per cent had completed higher education and more than 40 per cent hold a postgraduate degree or PhD, corresponding with a niche of the Serbian diaspora described by Prelec as “active diaspora”, i.e. those most interested in political processes in Serbia.

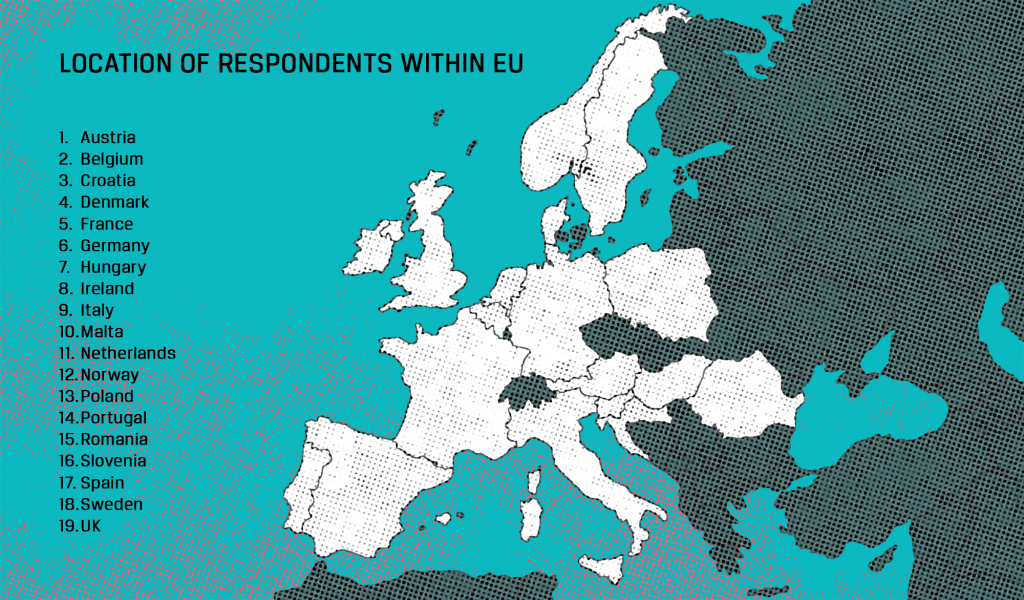

The survey covered 19 European Union member states, with the largest proportion of respondents coming from the UK.

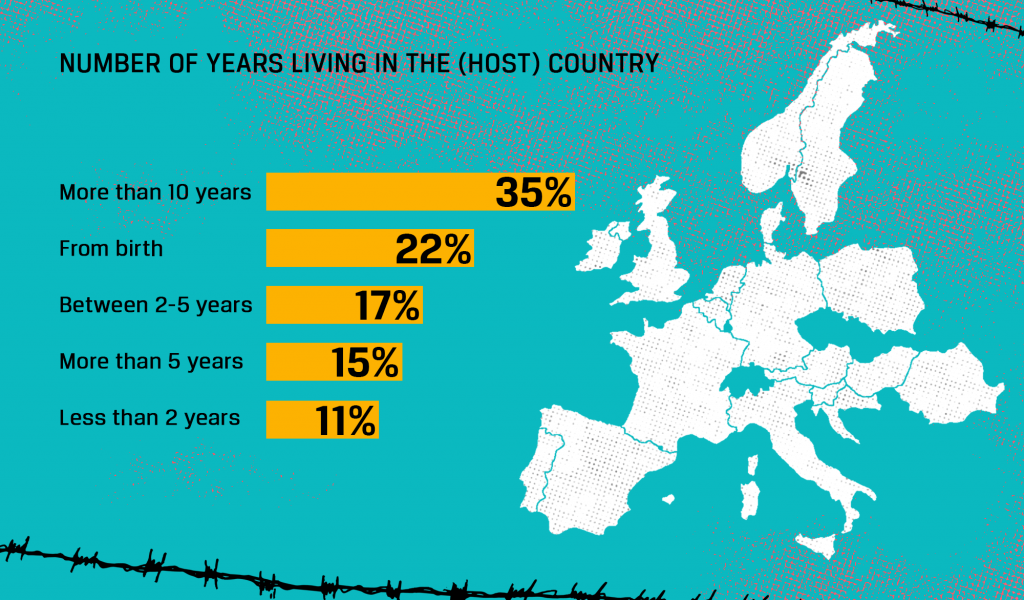

The sample is roughly divided between those who have been living abroad for more than ten years or from birth, and those living abroad for less than 10 years. The bulk of respondents are therefore not students but residents of their host countries.

A majority of respondents considered themselves informed about the political situation in Serbia and said they mostly use online media and/or social networks as their main sources of information.

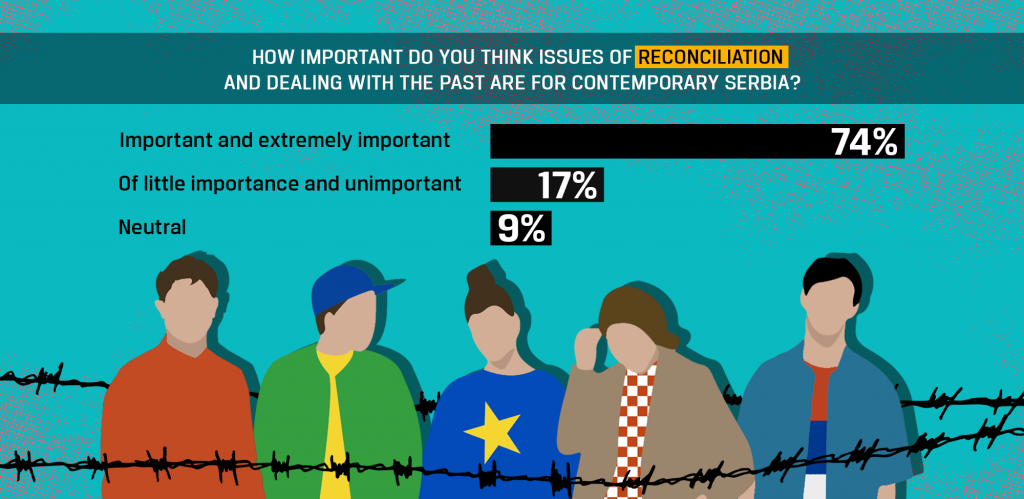

Almost three quarters [74 per cent] believe that reconciliation is important for Serbia.

The role of the Hague-based International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, ICTY, which wound up its work in 2017, is viewed mainly in negative terms, with almost 60 per cent disagreeing with the statement that the court played an important role in reconciliation in the region. This reflects the disputed legacy of the ICTY and the negative perception of it in all former Yugoslav countries involved in the conflicts of the 1990s.

Forty per cent identify Bosniaks as the ethnic group with most victims in the wars, 33 per cent said Serb casualties were highest and only one per cent said they thought Albanians died in most numbers.

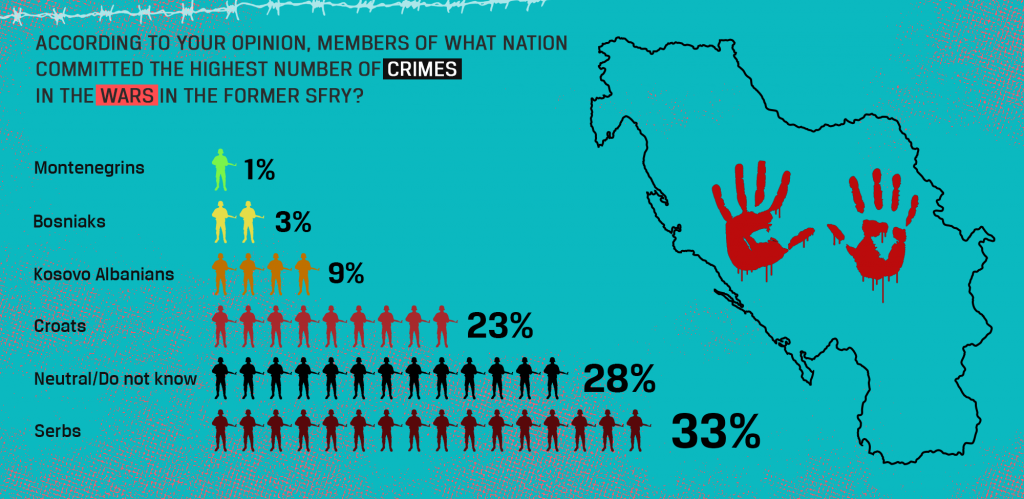

At the same time, one third [33 per cent] said they believed Serbs perpetrated most of the war crimes committed during Yugoslavia’s collapse.

Though the findings are not directly comparable, it is worth noting that a 2017 study in Serbia found that only five per cent of Serbians believe their kin were behind most of the war crimes, compared to 24 per cent who said Croats were mainly responsible [similar to the figure in this survey].

A strong majority [65 per cent] said they were against the rehabilitation of convicted war criminals and their participation in public and political life.

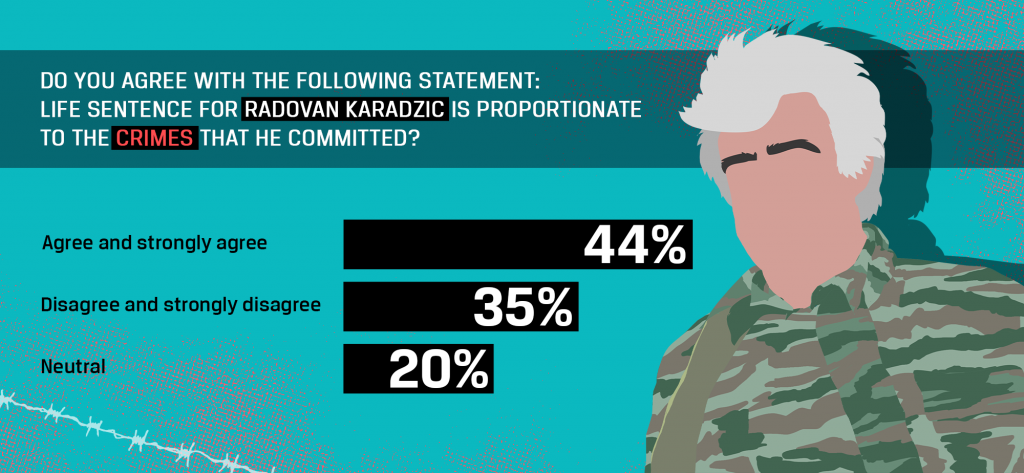

Fewer than half [44 per cent], however, said the life sentence received by Bosnian Serb wartime political leader Radovan Karadzic, convicted of genocide by the ICTY, was proportionate to the crimes he committed. Thirty-five per cent disagreed.

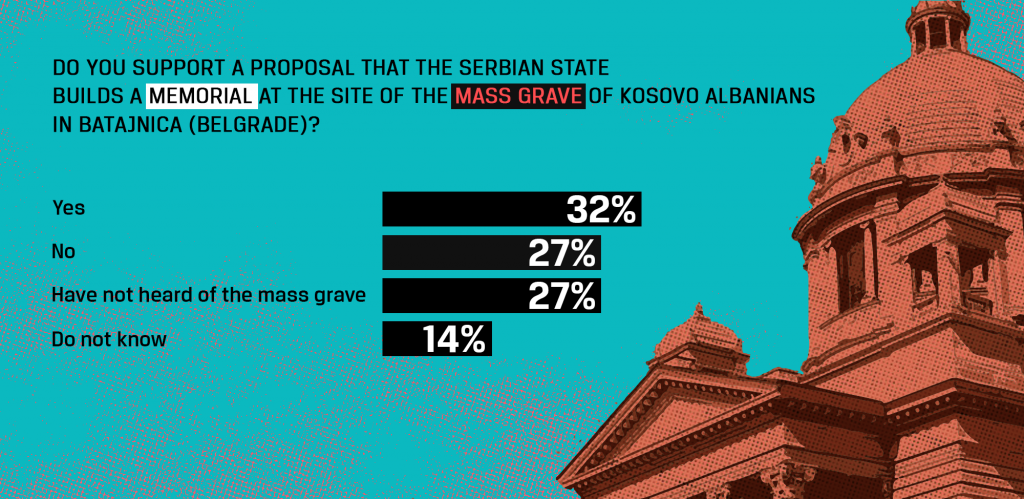

In 2001, months after the overthrow of Serbian strongman Slobodan Milosevic, the remains of more than 700 Kosovo Albanians were found buried in pits on the grounds of a training centre of Serbia’s anti-terrorist force in the Batajnica suburb of Belgrade, incontrovertible evidence of a systematic state effort to conceal war crimes committed during the 1998-99 Kosovo war.

For years, civil society organisations in Serbia have called for a memorial at the site.

Asked whether they support such an initiative, 41 per cent of respondents said they either did not have an opinion or had not heard of the Batajnica mass grave. Thirty-two per cent were in favour, and 27 per cent were against.

The survey revealed a range of responses. On the whole, diaspora respondents perceive reconciliation as important and demonstrate readiness to abandon the prevailing narrative in Serbia of exclusive Serb victimhood. They are also against the rehabilitation of convicted war criminals.

Yet the survey also suggests that the diaspora is not immune to trends within Serbia. Negative views of the ICTY are prevalent, while opinion is divided on Karadzic’s sentence and the Batajnica memorial.

For further insight, the author of this piece conducted a number of interviews with young Serbs living in the UK for at least five years.

Nebojsa, Tanja, Dusan…

Like Nebojsa, Tanja [not her real name] came from Belgrade to London for postgraduate studies, after which she decided to stay. Both have advanced in their respective careers, 31-year-old Tanja working in finance.

But while Nebojsa became fired up when discussing Serbia and the collapse of Yugoslavia, Tanja appeared more detached from developments at home and cool-headed in debate.

Unlike Nebojsa and Tanja, Dusan [also not his real name] comes from a small town in southwestern Serbia, lives in Bristol in southwestern UK and is married to a British woman. He is absorbed in running his own hair salon and did not appear to have a particular interest in politics.

What connected them all, however, was the fact they completed school in Serbia and, in the case of Tanja and Nebojsa, university education.

“I have family in Serbia and most of my friends,” Nebojsa said over coffee at Pret a Manger. “I go there two to four times a year and I vote in the elections, here at our embassy in London.”

Regarding regional relations, Nebojsa said he was “not an optimist.”

“With the current political situation in Serbia, Croatia and Bosnia, reconciliation is not possible,” he told BIRN.

“There is no doubt that Karadzic, [convicted Bosnian Serb war criminal Ratko] Mladic, [convicted Serbian war criminal Veselin] Sljivancanin, [ultranationalist Serbian politician Vojislav] Seselj, have committed terrible crimes, but there is also no doubt that hundreds of thousands of people have been expelled from their homes,” he said, in reference to Serbs who fled Croatia and Kosovo after the wars there.

Tanja, who agreed to meet at her office in a well-heeled neighbourhood of London, struck a more hopeful tone.

“I think reconciliation is very important, for the whole region, and especially for the people in Serbia,” she said. “We need to accept and acknowledge what we have done in the past.”

Nebojsa, on the other hand, said there would be no justice, and reconciliation was also unlikely.

“Justice for one person is not the same as the justice for the other person,” he said.

“The story always goes from Krajina [Serb rebel region during 1992-95 war from which up to 200,000 Serbs fled when it fell to Croatian forces], through Srebrenica to churches in Kosovo, then [Kosovo] Albanians will talk about the period before 1999 and we [Serbs] are all in 2004,” he said, in reference to Albanian mob riots against minority Serbs in Kosovo in March 2004.

“As a Serb, I will always first think what happened to my people. Justice will never come. And reconciliation will happen when we forget justice.”

Dusan also expressed caution:

“Looking at Kosovo, I don’t think there will be reconciliation. I have nothing against them [Kosovo Albanians], but I think they are malicious, and they [Kosovo Serbs and Kosovo Albanians] will not reconcile. When it comes to other nations, it seems to me that we are constantly giving in to those nations. They are all good and we are not.”

Both Tanja and Nebojsa echoed the negative view of the ICTY that emerged in the survey.

“Even though I didn’t follow it closely, the impression is that we were treated worse than everyone else in the region,” Tanja said. “Other criminals have either been released or received lesser sentences than our politicians.”

But the Batajnica memorial issue exposed their differences.

“And what about the Serbs expelled from Kosovo,” Nebojsa shot back when asked whether a memorial should be erected to Kosovo Albanians killed and subsequently buried in a pit on the outskirts of Belgrade.

Tanja, however, responded: “Yes, I think that would be a nice act and we should acknowledge crimes in this way through monuments. Maybe that symbolism can have a positive effect on young people in Serbia and our recognition of these crimes.”

The three agreed, nevertheless, that convicted war crimes should not enjoy rehabilitation.

Genocide denial

If the 1995 Srebrenica massacre became symbolic of Bosnia’s suffering at the hands of Serb forces, and the inability and unwillingness of the West to intervene effectively, what went on during those few July days, how many were killed and why continues to be disputed by many Serbs despite mountains of evidence compiled during multiple trials at the ICTY and in Bosnia.

In fact, there is almost blanket denial in Serbian society that the massacre constituted genocide, as ruled by the ICTY.

“I don’t think it was genocide,” Nebojsa said. “I don’t want to go now into what is the definition of genocide, but it was ethnic cleansing.”

He repeated an argument often heard in Serbia, that, “If they wanted to eliminate all of them and to commit genocide, they would have killed women too, not only boys and men.”

Dusan, however, disagreed.

“I think it was genocide. I cannot defend it and I am ashamed of it. You cannot kill that number of civilians, whether it was one thousand or five thousand it does not matter.”

Serbia came closest to contrition in 2010 when then pro-Western President Boris Tadic pushed a resolution through the Serbian parliament apologising for the massacre but stopping short of calling it genocide.

Current President Aleksandar Vucic is a former ultranationalist who, as prime minister, had to flee the annual commemoration at Srebrenica in 2015 after being hailed with insults and stones by those attending. In 2018, his handpicked prime minister, Ana Brnabic, said the massacre was a “terrible crime”, but not genocide.

In 2018, the European Parliament adopted a resolution condemning Serbia’s continued genocide denial, which remains a major obstacle to relations between Bosnia and Serbia.

“If Serbia made the gesture and acknowledged the judgment of the UN-based court, it would create enormous potential to give new impetus to reconciliation processes in the region,” said Hercigonja.

Nebojsa disagreed, however: “It would spread negative feelings among Serb victims of crimes, not only in Bosnia but elsewhere. Then one would wonder what is it that they did to us? This would create bigger problems.”

Out of sight, not out of reach

Conflicting narratives about the past continue to hold up reconciliation in Serbia and across the Western Balkans, perpetuating tensions.

Young people up to 35 years of age have few direct memories of the war period, while their understanding of what went on is shaped predominantly by education, the media and family members.

“In order to build an active attitude towards the difficult heritage of the past, it is necessary to first and foremost learn about that past,” said Visnja Sijacic of the Belgrade-based Humanitarian Law Centre.

“Young people should be brave enough to face the past and acknowledge the facts established by the court,” she said.

The reality, however, is that young Serbs’ understanding of the wars is limited and confused.

“Through the education system, young people are taught and informed about conflicts in a very bad way, in the sense that a narrative is created to make the Serbian side the biggest victim of conflict,” said Hercigonja.

The diaspora’s reliance on social networks and online media for information from Serbia and the region might suggest they are more able to develop opinions beyond the stifling reach of dominant, government-influenced outlets in Serbia itself such as the public broadcaster.

But Professor Dzeneta Karabegovic of the University of Salzburg in Austria said the same risks applied.

“It depends how these people use those social networks, what media they read, in which social groups they are active, who are the people they talk to,” Karabegovic said. “They can affirm their views and some romantic long-distance nationalist views in the same way.”

It should perhaps, therefore, not come as a surprise that, while their direct memories of Yugoslavia’s collapse are limited, young Serbs in the diaspora show some susceptibility to the dominant narratives in Serbia, an invented history glorifying Serbian struggle and victimhood.

Tanja, Nebojsa and Dusan each repeated a well-known negative perception of the ICTY that has been nurtured and shaped by Serbian media coverage of the court.

Nebojsa statements also reflected a collective, ethnic-based approach to justice and responsibility, present in all countries involved in the conflicts of the 1990s, rather than one based on individual accountability and responsibility.

For Luka Bozovic, a human rights activist, this is not surprising, particularly for the issue of Srebrenica:

“The official Serbian narrative is that if you say that it was genocide you are attacking Serbs as a nation, blurring individual responsibility,” Bozovic said.

“The question of Srebrenica [and the status of Kosovo] is so rooted in the understanding of the Serb national identity that belonging to a nation is measured in relation to political views.”

Thus, despite the liberal views of a significant number of young diaspora Serbs as found in this and other surveys, some of the strongest elements of the Serb nationalist narrative endure.

That young Serbs in the diaspora see reconciliation as important and are critical of the state of media freedom and the rule of law in Serbia will be seen as encouraging.

It confirms the potential for the diaspora to be an agent of change, bringing additional pressure to bear on the political elite to tackle the legacy of the wars and Serbia’s responsibility.

“The potential is clear,” said Prelec. “Minimise divisions and unite young people transnationally over common challenges.”

But the picture becomes more nuanced when touching upon specific issues that have begun central to the predominant Serbian narrative, such as Srebrenica and Kosovo.

For more than two decades, genocide denial has served to divide ‘proper’ Serbs from ‘traitors’ and ‘anti-Serbs’. The diaspora is not immune to this.

With the increasing migration of young people from the Balkans, the countries of the region must develop the mechanism and channels to encourage their engagement and involvement from abroad.

The involvement in young Serbian diaspora members in reconciliation efforts will help them confront their own prejudices and learn more critically about the past and what they have or have not been told over the past 30 years. Empowered with such knowledge, they should be encouraged to support structures and actors who promote such reconciliation and the holding to account of those responsible for war crimes.

Katarina Tadic has seven years of experience working in the civil society sector in Serbia.

Her research interests cover a variety of subjects including public administration reform in Serbia, democratisation and state-building in Kosovo, and gender equality-related topics.

As a Chevening scholar, she spent the past year in the UK studying MSc in Policy Research at the University of Bristol, doing a dissertation on domestic violence in Serbia.

This article has been produced as part of the Resonant Voices Initiative in the EU, funded by the European Union’s Internal Security Fund – Police.

The content of this story represents the views of the author and is the sole responsibility of BIRN. The European Commission does not accept any responsibility for use that may be made of the information it contains.

References

| ↑1 | Given the lack of a common definition, for the purposes here, diaspora is considered to be “individuals with distinct links (ethnic, social, cultural, economic) to a country of heritage other than their country of residence”. |

|---|