By Sophia Kluge

Introduction

Since 2015, the refugee debate has increasingly brought the topic of flight and migration into the media spotlight. Migration is a contested, emotionally charged, and highly politicised subject over which audiences in Europe are greatly polarised. The right-wing media in particular, have used the debate to criticise European migration policy. But how do these right-wing outlets contribute to the perception of refugees and migrants among their readers and how do they influence the public discussion?

Words hold great power and the choice of terms the media use when referring to migrants and refugees not only often encodes author’s and outlet’s political views, but in turn influences how other people perceive migration and its associated implications for the society as a whole.

An experiment at Stanford University conducted by psychologist Lera Boroditsky in 2011, explored how metaphors influence people’s reasoning about complex issues.[1]Thibodeau, Paul H.; Boroditsky, Lera. (2011). Metaphors We Think With: The Role of Metaphor in Reasoning. PLoS ONE 6(2): e16782. Available at: https://bit.ly/3dTVu1s She presented two groups of test subjects with a short report discussing the rapidly increasing crime rate in a fictional American city. Afterwards, people participating in the test were tasked with working out solutions to the problem.

Both groups read texts that were almost identical, with only one difference. One described crime in the city as a virus, the other one compared it to a beast. Participants who read the text using the virus metaphor, presented mainly preventive solutions and pleaded for educational programs and poverty reduction to address rising crime rates. The second group, who had read the metaphor of the beast in the report, advocated for a more restrictive approach, demanding stricter laws and higher prison sentences. Both groups justified their proposals with the figures and statistics in the article, which were exactly the same in both texts.

Boroditsky concludes “[…] that metaphors can have a powerful influence over how people attempt to solve complex problems and how they gather more information to make ‘well-informed’ decisions.” More importantly, “[p]eople do not recognize metaphors as an influential aspect in their decisions.”[2]Ibid., p.10

There are numerous real-life examples of the power and consequences of metaphors that have been evoked or propagated by journalists. In Germany, before the police discovered the background to a series of murders in the 2000s, which turned out to be committed by neo-Nazi terror group, the Nationalsozialistischer Untergrund (National Socialist Underground), the press kept referring to the murders as the so-called ‘Kebab Murders’, alleging a connection to organised crime, due to the immigrant background of the victims. Police likewise focused almost exclusively on the victims’ families and friends as suspects.[3]Fürstenau, Marcel. (09.09.2020). How the German media failed the victims of far-right NSU terror. Deutsche Welle. Available at: https://p.dw.com/p/3iDvC

The media and politicians similarly objectified refugees during the debate on the European asylum policy. By definining refugees as arriving in ‘flows’, ‘floods’ and ‘waves’, which creates ‘crises’, such negative terminology contributes to the dehumanisation of groups within the population.

Media can play a crucial role in reversing this trend. A great initiative in this direction, aiming to improve the way the media covers migration-related issues in Germany, is a glossary with new terms and expressions for an immigrant society, published by Neue deutsche Medienmacher*innen (New German Media Professionals)[4]NdM Glossar. (2020). Neue deutsche Medienmacher e.V. Available at: https://glossar.neuemedienmacher.de/, a nationwide, non-profit association of journalists committed to furthering diversity in the media.

It is, therefore, important to be aware of, and understand how, words can shape popular imagination about a particular group of people, and how they can become fodder for political battles. The following analysis of the German-language media will shed light on how this complex topic is covered in Germany, Austria and Switzerland. This brief will further explore how the German far-right, ultraconservative newspaper Junge Freiheit seeds derogatory neologisms about refugees, which spread through mainstream media, poisoning the public debate.

or scroll down to read more

Refugees and migrant-related discourse in the media ecosystem

In analysing the frequency of the usage of migration-related terms in the newspaper media, a clear trend can be observed from 2013 onwards: a significant increase in occurrence of the word “refugees” in German-language media. The reporting on the subject of flight began increasing in 2013, picking up pace in 2014 and peaking in 2015, after which it remained prevalent, with some fluctuations, until 2018, when it began declining (Figure 1).

However, with the increase in the reporting on refugees, and the rise in the numbers of refugees arriving, particularly in Germany, the number of reports on racism and especially xenophobia has, according to the data, hardly changed since 2010, even though more pejorative and derogatory synonyms have entered the so-called discursive arena, too.

The German newspaper Junge Freiheit’s print circulation has significantly increased since the founding of the right-wing party AfD, particularly since the rise to prominence of the refugee debate in 2015 (Figure 2).

What is Junge Freiheit?

With reference to a study from 2003[5]Dietzsch, Martin; Jäger, Siegfried; Kellershohn, Helmut; Schobert, Alfred. (2003). Nation statt Demokratie. Sein und Design der „Jungen Freiheit“. Unrast Verlag, Duisburg., Junge Freiheit “[…] has deliberately settled in a ‘border area’ between anti-constitutional right-wing extremism and that spectrum of conservatism and nationalism that was still within the ‘constitutional arc’.” Between 1993 and 2004, Junge Freiheit was monitored by the Office for the Protection of the Constitution of the State of North Rhine-Westphalia[6]Pfeiffer, Thomas; Puttkamer, Michael. (2007). Warum das Land Nordrhein-Westfalen die „Junge Freiheit“ in seinen Verfassungsschutzberichten geführt hat. In: Braun, Stephan; Vogt, Ute., (Eds). Die Wochenzeitung “Junge Freiheit”. Kritische Analysen zu Programmatik, Inhalten, Autoren und Kunden. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden. pp.57-74, p.57. Since then, the newspaper has become more moderate, but nevertheless “[…] a radically formulated and ethnically based nationalism can be recognized”[7]Botsch, Gideon. (11.01.2017) Die Junge Freiheit – Sprachrohr einer radikal-nationalistischen Opposition. Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung. Available at: https://bit.ly/3onRE5F. Junge Freiheit ties in with the zeitgeist of political-ideological currents of the pre-war and inter-war period and “remains to be an important mouthpiece of a radical nationalist opposition that is concerned with a fundamental change in the social, political, and cultural conditions in Germany”[8]Ibid..

The frequency of reporting on migrants and refugees in Junge Freiheit is very similar in comparison to the mainstream media (Figure 2). Worth noting also, is that even before 2015, Junge Freiheit reported on migrants and refugees at a constant level.

Junge Freiheit does not moderate its readers’ forums. Readers of Junge Freiheit often refer to migrants and refugees using insulting language, although these derogatory terms themselves rarely appear in the articles. A closer look at their readers’ forum offers a glimpse into the right-wing/nationalist political spectrum sympathisers’ and voters’ perception of migrants and refugees (Figure 4).

Declaring refugees as uninvited [ungebeten], as scammers [Betrüger] and as being bogus [Schein] questions their credibility and the legitimacy of their asylum claims or migration status. The usage of the words such as occupiers [Okkupanten], border violators [Grenzverletzer], invaders [Invasoren] and intruders [Eindringlinge], indicates a hostile attitude towards refugees, perceiving them as a security threat.

The relationship between media articles and reader comments and attitudes is generally quite complex. Readers with certain attitudes self-select stories which confirm their views, so it is difficult to conclude that their opinions are changed rather than merely reinforced by the exposure to migration-unfriendly fear mongering content in the right-wing media. Creating a space where those attitudes can be reinforced by peers, such as in the readers’ comments, however, can be considered as more directly contributing to radicalisation and mobilisation.

Figure 5 broadly supports this assumption: the terms that appear in the Junge Freiheit’s readers’ comments, also appear in the newspaper’s articles itself. This applies above all to the term “asylum seekers” [Asylanten][9]“Asylbewerber” and “Asylant” both translate as “asylum seeker” in English. ‘Asylbewerber’ is the official and politically correct term, whilst the less correct ‘Asylant’ is purposefully used nowadays across the right-wing spectrum., which – albeit to a lesser extent – was part of the reporting even before the refugee debate became present in European media.

Secondly, within the media ecosystem, discourse, themes, frames, images, symbols, metaphors and other related terminology that exist on the fringe, can be pushed to the mainstream, for example when moderate newspapers report about the increased use of those terms by the far right.

In examining since 2010, a total of 170, mostly moderate, main-stream media German-language newspapers in Switzerland, Austria and Germany for their use of the terms identified in the Junge Freiheit’s forum, it can be observed that some of these terms have started to appear more frequently since 2014/15. There are spikes in 2015 and then again in 2018 in the use of the term economic refugees [Wirtschaftsflüchtlinge] and the term Invaders [Invasoren].

The terms occupants [Okkupanten], bogus asylum seekers [Scheinasylanten] and asylum seekers [Asylanten], on the other hand, are rarely used in mainstream media reporting.

In interpreting these results, a caveat should be kept in mind; they contain “false positives” because a simple word count does not take into consideration the context of use. For example, the term ‘invaders’ is also found in articles that do not refer to present day refugees, discussing historical events, film reviews. Additionally, articles criticising and problematising this terminology are also included in the count.

The remaining insulting terms discovered in Junge Freiheit’s readers’ forum appear even more rarely or are too ambiguous and are therefore not plotted in the graph.

Readers’ comments on migrants and refugees

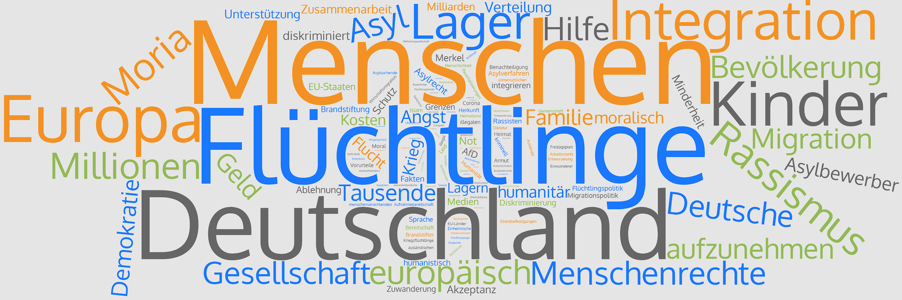

The last part of the analysis looks at the content of the Junge Freiheit’s unmoderated readers’ discussions under articles covering migration related issues.[10]Only the reader comments on Junge Freiheit’s website were examined, not those on social media sites such as Facebook or Twitter. It visualises the terms commonly used to refer to migrants and refugees, presented in Figure 3 above, in the context of their associated words.

For contrast, the findings are compared to the analogous visualisation of words found in the comments section in the left-liberal newspaper Die Zeit, under articles on migration in the same period, between August and September 2020.

Source: Junge Freiheit; own calculations

Source: Die Zeit; own calculations

The difference between the most commonly used terms in the discussion under articles about migration in these two outlets is striking and quite telling. These two word-clouds roughly represent the two worldviews: one open and inclusive, the other closed and exclusionary. These views and attitudes are continuously reinforced through content produced by, and communities supported by, these two media outlets.

The dominant terms differ significantly between the two outlets’ readership communities. In the forum of Junge Freiheit, the adjective Deutsch [German] clearly dominates as the most frequently used word. Second most used term is Chancellor Merkel’s name and the Green party [Grüne], presumably as frequent targets of criticism. The word ‘people’ meant in the sense of a national community [Volk], appears as commonly as the word Police [Polizei].

In the discussions in Die Zeit, the people are referred to as humans [Menschen] and together with the country’s name [Deutschland], and refugees [Flüchtlinge]. These represent the three most frequently used words. To a lesser degree, Europe [Europa], integration and children [Kinder] are also frequently mentioned by readers of Die Zeit.

Explaining the Volk

The concept of the Volk became important in the early modern period during the course of the German nation-building process. For Johann Gottfried Herder, one of the most influential German writers and thinkers in the Age of Enlightenment, the people [Volk] are an original, natural, ancestral, cultural and political community, with specific qualities and characteristics”.[11]Geier, Andreas. (1997). Zum Verhältnis von Staat, ‘Nation’ und ‘Volk’. In: Hegemonie der Nation. Deutscher Universitätsverlag, Wiesbaden. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-663-10291-5, pp70-85, p.71 “[…] Often described as the founder of nationalism, and more specifically of a genealogical and organic view of the nation tending toward ethnonationalism”[12]Eggel, Dominic; Liebich, Andre; Mancini-Griffoli, Deborah. (2007). Was Herder a Nationalist? The Review of Politics69(1). Available at: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0034670507000319, pp.48-78. p.50, Herder and his concept of nation were reinterpreted and instrumentalised by the Nazis in order to spread their ideology throughout the educated middle class.

The destructive character of this interpretation culminated in the brutality of National Socialism[13]Ibid., during which the concept of the Volk was used excessively. Through language, the Nazis constructed the people [das Volk] as an organic whole of culture, history and race. Volk – a term that once helped to unite and integrate people into a common nation turned into a means of exclusion and cultural dominance.

Today, the AfD “is rehabilitating terms that were contaminated by National Socialism” and “the far right and others have started distinguishing between ‘passport Germans’ and ‘bio-Germans'” again, Katrin Bennhold points out in an article for New York Times.[14]Bennhold, Katrin. (08.11.2019). Germany Has Been Unified for 30 Years. Its Identity Still Is Not. The New York Times.Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/11/08/world/europe/germany-identity.html

An illustrative example of this exclusionary world and the use of the term Volk in this context can be seen in the Junge Freiheit’s readers’ forum. A reader reacts to an article from 2 September 2020 reporting that Germany’s Interior Minister Horst Seehofer wants to take targeted action against Islamophobia in Germany[15]Seehofer sagt Islamfeindlichkeit den Kampf an. (02.09.2020). Junge Freiheit. Available at: https://bit.ly/2HmUsiZ. The article reports that as a response to the right-wing extremist attack in Hanau the German government decided to set up a committee that will prepare within two years a report with recommendations for the fight against hostility towards Muslims.

He [Horst Seehofer] does not declare war on the Arabs who hate our country, rape our women, and violate the people [das Volk]. NO!!!! It’s the evil right. The political caste should be completely disposed of.[16]Original: “Er sagt nicht den Arabern, die unser Land hassen, unsere Frauen vergewaltigen, und das Volk mit Gewalt überziehen den Kampf an. NEIN!!!! Es sind die pöööööhsen Rrrrrechten. Die Politkaste gehört insgesamt komplett entsorgt.”

Junge Freiheit took no action to remove this, and many similar comments, from its website.

In contrast, a long-term observation of the readers’ discussions in the German left-liberal leaning mainstream newspaper Die Zeit reveals that despite the fact that the readers criticise Germany’s refugee policy here too, such derogatory terms do not appear. Moderators delete such posts, if necessary, referring to the forum guidelines in connection with hate speech.

Conclusion

This advisory brief, based on an analysis of German-language media in Germany, Austria and Switzerland, has attempted to highlight some of the problems related to media reporting and the media’s own reader comment-moderation practices in the context of migration-related public discussions. It combines insights from long-term observation of the online community of readers of Junge Freiheit and Die Zeit, with quantitative time-series data from large media datasets taken from Media Cloud.

Secondly, the brief also endeavoured to introduce several different assessment lenses and techniques through which it may be possible to capture the emergence and spread of problematic language and framing in public discussion. These can, consequently, reinforce dangerous trends in the perception of migration, as well as migrants and refugees; the framing of policy options and preferences and, importantly, in the mobilisation around them, including through voting or direct action.

The media can play a great role in preventing this damage, through both their own reporting and shaping of the narrative; their framing of the discussion and, through managing their online communities, without stifling freedom of expression and healthy criticism. By failing to moderate discussions under their own reports in the readers’ forums in particular, the newspaper contributes to the fertilisation and festering of dangerous stereotypes, radicalisation, and mobilisation.

Finally, the above has shown how different problematic terms, from generalizing statements, to dehumanising, humiliating, insulting and racist expressions in reference to refugees, migrants, or foreigners in Germany circulate in the media ecosystem and trickle down to readers, possibly causing long term damage to public discussion about migration policies and, to the fabric of the society.

This article has been produced as part of the Resonant Voices Initiative in the EU, funded by the European Union’s Internal Security Fund – Police.

The content of this article represents the views of the author and is his/her sole responsibility. The European Commission does not accept any responsibility for use that may be made of the information it contains.

References

| ↑1 | Thibodeau, Paul H.; Boroditsky, Lera. (2011). Metaphors We Think With: The Role of Metaphor in Reasoning. PLoS ONE 6(2): e16782. Available at: https://bit.ly/3dTVu1s |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Ibid., p.10 |

| ↑3 | Fürstenau, Marcel. (09.09.2020). How the German media failed the victims of far-right NSU terror. Deutsche Welle. Available at: https://p.dw.com/p/3iDvC |

| ↑4 | NdM Glossar. (2020). Neue deutsche Medienmacher e.V. Available at: https://glossar.neuemedienmacher.de/ |

| ↑5 | Dietzsch, Martin; Jäger, Siegfried; Kellershohn, Helmut; Schobert, Alfred. (2003). Nation statt Demokratie. Sein und Design der „Jungen Freiheit“. Unrast Verlag, Duisburg. |

| ↑6 | Pfeiffer, Thomas; Puttkamer, Michael. (2007). Warum das Land Nordrhein-Westfalen die „Junge Freiheit“ in seinen Verfassungsschutzberichten geführt hat. In: Braun, Stephan; Vogt, Ute., (Eds). Die Wochenzeitung “Junge Freiheit”. Kritische Analysen zu Programmatik, Inhalten, Autoren und Kunden. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden. pp.57-74, p.57 |

| ↑7 | Botsch, Gideon. (11.01.2017) Die Junge Freiheit – Sprachrohr einer radikal-nationalistischen Opposition. Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung. Available at: https://bit.ly/3onRE5F |

| ↑8, ↑13 | Ibid. |

| ↑9 | “Asylbewerber” and “Asylant” both translate as “asylum seeker” in English. ‘Asylbewerber’ is the official and politically correct term, whilst the less correct ‘Asylant’ is purposefully used nowadays across the right-wing spectrum. |

| ↑10 | Only the reader comments on Junge Freiheit’s website were examined, not those on social media sites such as Facebook or Twitter. |

| ↑11 | Geier, Andreas. (1997). Zum Verhältnis von Staat, ‘Nation’ und ‘Volk’. In: Hegemonie der Nation. Deutscher Universitätsverlag, Wiesbaden. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-663-10291-5, pp70-85, p.71 |

| ↑12 | Eggel, Dominic; Liebich, Andre; Mancini-Griffoli, Deborah. (2007). Was Herder a Nationalist? The Review of Politics69(1). Available at: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0034670507000319, pp.48-78. p.50 |

| ↑14 | Bennhold, Katrin. (08.11.2019). Germany Has Been Unified for 30 Years. Its Identity Still Is Not. The New York Times.Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/11/08/world/europe/germany-identity.html |

| ↑15 | Seehofer sagt Islamfeindlichkeit den Kampf an. (02.09.2020). Junge Freiheit. Available at: https://bit.ly/2HmUsiZ |

| ↑16 | Original: “Er sagt nicht den Arabern, die unser Land hassen, unsere Frauen vergewaltigen, und das Volk mit Gewalt überziehen den Kampf an. NEIN!!!! Es sind die pöööööhsen Rrrrrechten. Die Politkaste gehört insgesamt komplett entsorgt.” |