By Nenad Radičević

Introduction

On 31 May 2020, US President Donald Trump tweeted his intent to designate Antifa a terrorist organisation, leading to a massive spike in the online media coverage and also in the internet user interest around the world, including in the Balkans.

However, the context of public discussion about Antifa and anti-fascism in the Balkans is very different than that in the United States. In the Balkans, the spotlight on the movement and its association with terrorism, as per the leader of the free world, fuelled the already present ideological battle surrounding the anti-fascist legacy in the former Yugoslavia, emboldening local supporters of the far-right on social media.

When it comes to debating Antifa in the countries of former Yugoslavia, considerable effort has been made in promoting a narrative that intentionally conflates communism, particularly the crimes committed by the communist regime with the region’s deep anti-fascist tradition, thus discrediting the latter. This ‘tradition’ long precedes the movement’s contemporary infamy in the US, relating to the Black Lives Matter (BLM) protests.

Without achieving the virality of Donald Trump’s anti-Antifa tweet, the resolution of the European Parliament (EP) from 19 June 2019, entitled ‘European Parliament resolution of 19 September 2019 on the importance of European memory for the future of Europe’[1]European Parliament resolution of 19 September 2019 on the importance of European remembrance for the future of Europe (19/07/2019). European Parliament. Available at: https://bit.ly/2TwajhG, has also become a useful tool in targeting and defaming anti-fascism in the region.

This Advisory Brief discusses the impact both the BLM/Antifa and the EP Resolution-inspired online discussions on anti-fascism have had in the Balkans and throughout the Balkan diaspora communities around the world. The document focuses on exposing the narrative tactics, key arguments, tropes, symbols, and imagery that were weaved into a web of online manipulation, connecting many individual content pieces.

or scroll down to read more

Localising the culture war

In his divisive Independence Day speech on Mount Rushmore, Donald Trump, in a bid to fire up his voter base, darkly warned of an impending culture war, describing Antifa and the BLM protests as a “leftist culture revolution” intent on rewriting national history. He has since doubled down in his portrayal of the security threat posed by Antifa and the radical left, while only hesitantly denouncing white supremacists. As a result, Trump’s announcements that he would declare Antifa a terrorist organisation, were used as ammunition by the supporters of the far-right on social media in the ongoing ideological battle around the anti-fascist legacy in the former Yugoslavia.

Given the prominence of the speaker, it is no wonder that this message was widely translated – by activists, politicians, celebrities and ordinary social media users alike. They applied them – often creatively – to local contexts in their online communication, as well as to offline actions underpinning ongoing local struggles against fascism adapting them to make them relevant to intractable regional conflicts and progressive/conservatives causes more broadly. The dominance of the USA’s domestic social conflict in the global media, inspires activists sympathising with different groups to draw parallels with their own local conflicts, in an attempt to put their issues in front of larger audiences and on the decision makers’ agenda.

The strategy of drawing parallels between the BLM protests and local events, by using BLM vocabulary and imagery, was widely employed by a range of actors, from heads of states to anonymous commenters on social media. For example, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan told the American President in a phone call that Kurdish groups in Turkey and Syria were linked to Antifa and other groups that were behind the violence during the protests in the USA.[2]Goodenough, P. (2020). Turkey’s Erdogan Seeks to Link Antifa in US With US-Allied Syrian Kurdish Fighters. CNS News. Available at: https://bit.ly/2HISJUF

A few common themes clearly emerged from these efforts to localise and re-contextualise the main narratives, language, and imagery associated with the current social unrest in the United States. These processes have been monitored and analysed by the Resonant Voices Initiative as they played out in the digital media ecosystem. In the process of culture war localisation, intractable local conflicts are inflamed, organically and artificially, intentionally and unintentionally.

Contested cultural heritage

The toppling of statues in the USA ignited a discussion on the parallels with Serb and Croat extremists destroying mosques and monuments from the Ottoman Empire in Bosnia and Herzegovina during the wars of the 1990s. This prompted endless polemics about who destroyed more of whose monuments during the war and led to the comparing of Antifa activists with Balkan war criminals.

Serbs in Montenegro used the BLM protests to highlight their cause and the ongoing protests for the protection of the Serbian Orthodox Church’s religious objects in Montenegro. Authors of the post below complain about the media’s double standards in reporting on their peaceful demonstrations as retrograde and barbaric, while the violent BLM protester are seen as defenders of democracy.

Among right-wing social media users in Serbia, the BLM and Antifa protests were used to support a broader message about racism in the West and to fuel anti-Western sentiment.

Discrimination against minorities

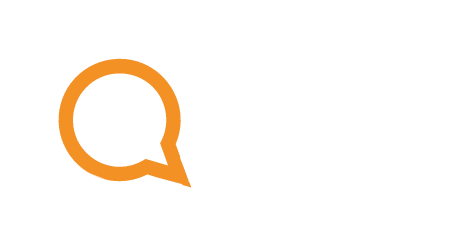

Pictured below, Croatian writer Igor Mandić and Serbian political analyst Nemanja Starović, separately used a newly-coined slogan “Serb Lives Matter” in their articles/posts to highlight local interethnic problems in Croatia and Montenegro.

Internet users were frequently suggesting online that “Serb Lives Matter” protests should be organised in Croatia and Montenegro or “Roma Lives Matter” in Serbia or “Migrant Lives Matter” in Germany.

Diaspora mobilisation

The Albanian/Serbian divide was visible in the online exchanges within and between the Albanian and the Serb diasporas about the BLM protests in the USA. Some users on social media drew parallels between the treatment of Albanians in the Balkans and that of Black Americans in the United States, pointing out that the Albanians were victims of similar state repression and ethnic hatred.

A portion of the Serb diaspora came out in defence of President Trump’s statements and actions in relation to the BLM protests on social media, while the Albanian diaspora often criticised him and expressed support for his election opponent Joseph Biden instead. Members of the Serb community in the USA started the Facebook campaign “Serbs for Trump 2020” with the aim of motivating a million of Americans of Serbian descent to engage in Trump’s re-election.

A Twitter post containing a photograph from the protests in Chicago showing two children carrying banners with a message “End to racism. Kosovo is Serbia” prompted fierce reactions from the Albanian community. Even though it was quickly removed by the Twitter user who originally posted it, the photograph was shared on numerous portals across the region.

Imported conspiracy theories

Just as the social conflict in the US is translated and interpreted through the prism of local conflicts, local conspiracy theorists look for also draw inspiration from the US as they search for signs of conspiracy in their local context.

Some far-right commentators in the Balkans have fully adopted the QAnon rhetoric, interpreting the BLM protests being as orchestrated by the American “deep state”, the radical left, powerful bankers, George Soros and a few other American billionaires, as well as a network of parties, radical movements, NGOs and individuals across the world.

The Russia-sponsored Sputnik Srbija, with assistance from the alt-media ecosystem, contributed to spreading these conspiracies in the Balkans and among their diasporas.

Serbia’s many tabloids and alternative media declared the Antifa and BLM protests responsible for the changes in the USA’s foreign policy toward the Kosovo-Serbia issue. According to them, the BLM protests were engineered by the “deep state” and billionaire George Soros in order to prevent Donald Trump from taking a more pro-Serbian stance in negotiations between Belgrade and Pristina.

Distorting Europe’s anti-fascism message

While the original messaging from Donald Trump on Antifa, in the context of the BLM protests, is often transmitted verbatim because it fits the existing right-wing narrative on anti-fascism in the Balkans, the aforementioned Resolution on the importance of European remembrance for the future of Europe (the Resolution), is also frequently cited by the ethno-nationalist leaning alternative media, who distort and misinterpret it heavily.

The Resolution’s text condemns the crimes of both the Nazi and communist totalitarian regimes and all manifestation and propagation of totalitarian ideologies. The right-wing spin doctors now commonly use it in their narrative, which is built around the false equation of communism (and especially communist crimes against humanity), with the region’s anti-fascist struggle.

Despite the intention and motivation of European lawmakers in drafting the Resolution, and the symbolic value of this document notwithstanding, it has regrettably been very skilfully weaponised by right-wingers in two EU member states – Croatia and Slovenia along with their EU membership-aspiring neighbours in the Balkans. It is used against anti-fascists and all those fighting against attempts to relativise Ustasha crimes and the role of the Ustasha regime in Croatia in the Second World War.

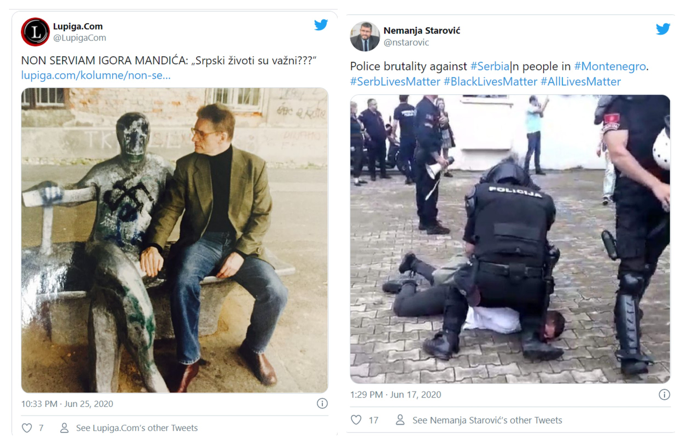

An epitome of their flawed logic is the claim, citing the EP Resolution, that the five-pointed star, which was on the flag of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (and all it’s states) and was worn by partisans during the WW2 and used as a symbol of resistance against Nazi occupation, should be banned as a symbol of totalitarian regime.

Paradoxically, according to right-wing activists in Croatia, the five-pointed red star should be treated (i.e. banned) in the same way like Nazi swastika was, while at the same time, they fight tooth and nail to defend and preserve the symbols associated with the Nazi-collaborating Croat state, such as the controversial “Za dom spremni” (Ready for the Homeland) salute, used by the Ustasha.

There is an ongoing, concerted effort in the right-wing online media space to advocate for the “implementation of EP Resolution” by removing every sign of communist history in Croatia. Arguments selectively referencing the EP Resolution are used against leftist politicians, associations, and activists, and also to criticise the moderate conservative Croatian Prime Minister, Andrej Plenković.

The photo collage below contains an example of titles that focus on the leader of Yugoslav partisans and later President of Yugoslavia Josip Broz Tito, who is in these outlets often equalised with Adolf Hitler and Joseph Stalin. In this context, they accuse Croatia’s PM of not wanting to implement the EP Resolution in order to avoid “overthrowing Tito’s myth” and removing Tito “from the pedestal of antifascist fight.”

The texts and posts referencing the resolution conveniently leave out parts which do not suit the far-right narrative. For example, they fail to mention that the EP expressly “condemns historical revisionism and the glorification of Nazi collaborators in some of the EU Member States, or that the EP “calls on the Member States to condemn and counteract all forms of Holocaust denial, including the trivialisation and minimisation of the crimes perpetrated by the Nazis and their collaborators, and to prevent trivialisation in political and media discourse.”

The coverage and arguments that use the EP Resolution, likewise do not convey the deep concern expressed by the EP about “the increasing acceptance of radical ideologies and the reversion to fascism, racism, xenophobia and other forms of intolerance in the European Union,” and the “collusion between political leaders, political parties and law enforcement bodies and the radical, racist and xenophobic movements of different political denominations”.

Defenders of Anti-fascism

There are many voices that call out the manipulation of these weaponised and distorted narratives and messages circulating in the vast media ecosystem. However, because of the success that bad-faith actors have had in exploiting existing trust deficits, cognitive biases, and platform features, these voices need boosting.

Mainstream media and fact-checkers

The right-wing uses a recognisable set of terms and tactics to undercut the credibility of mainstream media reporting. German right-wingers from the Alternative for Germany use the term “lying press” (Lügenpresse), an expression coined by the Nazis (when they came to power in the 1930s) in order to discredit critical media. In Croatia, mainstream media are labelled as “yugo-communist” and “extremely leftist”. In Serbia, they are accused of “belonging to Soros”, as “globalist” and “belonging to the regime.”

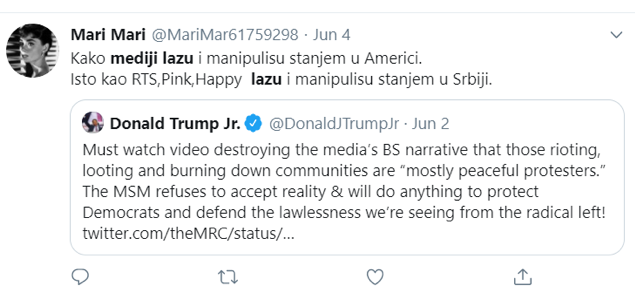

The ongoing, consistent “fake news” messaging of Donald Trump resonates with the audiences in Serbia, who draw parallels to similar behaviour of public broadcasters and mainstream media.

Besides the mainstream media, fact-checking organisations and portals exposing disinformation are increasingly targeted by members of the far-right, and by advocates of populist policies and conspiracy theories. This is visible in Croatia, where the far-right often accuses the portal Faktograf.hr of “filtering the truth about mass and systematic communist crimes and declaring them to be historical revisionism, while declaring falsified yugo-communist history as truth”.

Influencers

With confidence in the media at an all-time low, some public figures from the region came out in support of the BLM protests and the wider progressive agenda, attempting to pierce through the noise and reach audiences from beyond their own echo chambers.

Many who tried this, ended up experiencing a backlash on social media when attempting to translate the BLM struggles into local contexts and local politics, or relating them to their personal lives.

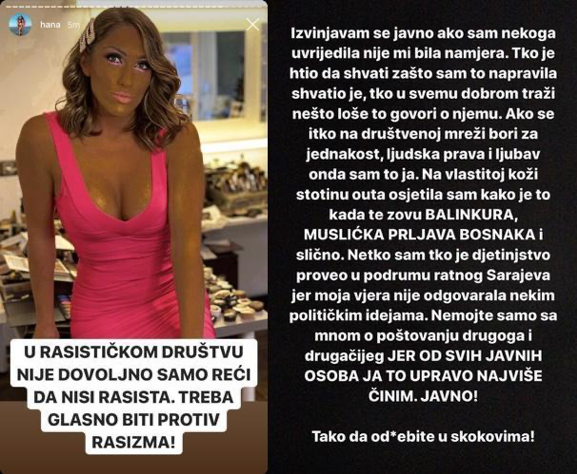

The most visceral example was the reaction to a photographer, journalist, and social media influencer in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Hana Hadžiavdagić Tabaković, who has 567.000 followers of her Instagram profile. As an expression of support, she posted on her Instagram profile a photo of herself in which she darkened her skin colour. The photo was overlaid with a quote “in a racist society it is not enough to say you’re not a racist, one needs to be loudly against racism.”

Despite the fact that Tabaković quickly removed the controversial photograph and posted an apology claiming that she herself had been an object of discrimination, her photo found its way to an audience of millions in international media, even on Reddit, which is not so popular in the Balkans. Her photograph soon appeared on numerous platforms, reaching millions of viewers, prompting thousands of mostly insulting comments. Some commenters also used this incident as a springboard to attack leftist and liberal ideological views, as well as the BLM movement itself.

Famous Serbian basketball player Vlade Divac, who appeared at the BLM protests in California together with his family (pictured above), sparked a heated debate on Twitter. In this case, his presence was interpreted within the context of Divac’s alleged responsibility for Kosovo joining the International Olympic Committee, at the time when he was the president of the Olympic Committee of Serbia.

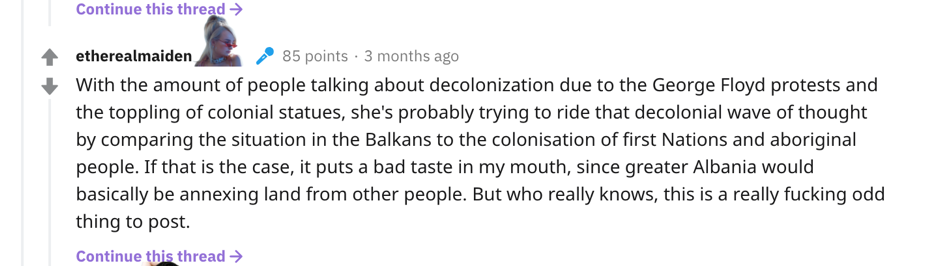

Another mega-celebrity with roots in the region, award-winning singer Dua Lipa, sent nationalists across social media into a frenzy with a post that showed a map of “Greater Albania.”[3]See Resonant Voices Radar for a more in-depth analysis She also made pop music fans outside the region wonder about the motivation behind her posts, as this example from a subreddit called Popheads shows.

While there may be advantages to celebrities raising the profile of regional struggles, there are downsides to their often-simplified interpretations of history, which include the stirring up of ethno-nationalist debates.

Historians

To counter the rampant historical revisionism in the region, the declaration Defend history[4]Defend History: Declaration. (2020). Udruženje Krokodil. Available at: https://bit.ly/2HEeo0E was published in Belgrade in June 2020. Developed by a group of eminent local historians within the framework of the project “Who started first? – Historians against revisionism”, the declaration demands of historians that they adhere to the highest scientific standards in their discipline, especially when dealing with sensitive and controversial topics. It also calls on the political elites to “stop abusing the past and do not lean on historians, intellectuals and interest groups that fuel nationalist passions, putting us into conflict with each other for the sake of strengthening their political position.”

The appeal of the authors and signatories that the study of history should not be abused, is also addressed to the courts, ministries, media, local authorities and, history teachers. Further, it asks local parliamentarians and the European Parliament, not to pass acts “which would impose a ‘historical truth’ and a suitable interpretation of the past, because by doing so they directly partake in the rewriting of history and in dangerous manipulations with the past.”

Though the declaration has not provoked as fierce a reaction in the region as the Declaration on a common language[5]Deklaraciju o Zajedničkom Jeziku. (2017). Udruženje Krokodil (et al). Available at: https://bit.ly/34wv2rR published three years ago did, some Croatian nationalist media outlets and blogs immediately went on an offensive, evoking conspiracy theories (see text box below) and slandering the initiative as an attempt to discredit the EP Resolution about the importance of European memory for the future of Europe.

Second Memorandum of the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts (SANU) conspiracy

One of the arguments used against Defend history is that it is being linked with the so-called Second Memorandum of the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts (SANU).

This alleged document has circulated extensively online for years, not just on social media but also in mainstream media in Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina. It suggests that Serbian intellectual and political elites are secretly advancing the ethno-nationalist and expansionist ‘Greater Serbia’ policies of 1990s, including a plan to stir instability in Bosnia and Herzegovina in order to push the secession of its Serb-dominated entity, Republika Srpska. However, the existence of the so-called Second Memorandum has never been proved, and previously published facsimiles of this document indicate that the probability of it not being an authentic document, is very high.

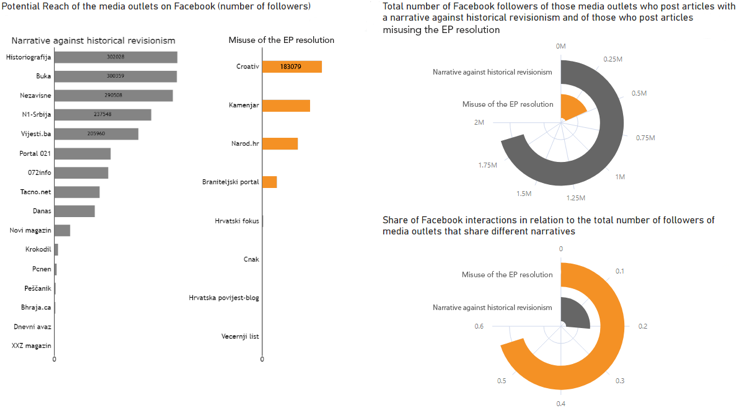

The figure below presents the analysis of the likely impact of the two narratives in the online environment: the one supportive of the declaration “Let’s defend history” and the other one that overtly supports the EP Resolution, using its distorted interpretation.

On the one hand, the online articles that support or promote the historians’ declaration managed to reach almost four times more Facebook users than the articles whose messaging misinterprets the EP Resolution. On the other hand, the narrative misinterpreting and misusing the EP resolution inspired many more Facebook users to actively engage.

Conclusion

Many actors within the digital media ecosystem, monitored by the Resonant Voices Initiative in 2019-2020, use different narrative-manipulation tactics to polarise audiences in the Balkans, and across the Balkan diaspora, along the multiple fault lines reflecting the ethnic, political, or religious affiliations of these diverse communities.

The analysis of social media posts and media articles demonstrated how global events, and their subsequent reactions and initiatives, trickle down into more localised debates about contemporary fascism and anti-fascism and how misinformation and propaganda contribute to the stoking of local conflicts. This brief presented and summarised various elements and features of these manipulation tactics.

It presented the scale and the depth of the right-wing attack on anti-fascism in the Balkans, and the current limitations of the counternarratives, requiring a more coordinated, long term response.

Resisting and pushing back against the efforts to undermine and discredit anti-fascism starts, and continues, through cooperation between a wide range of actors to bring about democratic social change and to address grievances and rights violations, as the best antidote to violent extremism.

This article has been produced as part of the Resonant Voices Initiative in the EU, funded by the European Union’s Internal Security Fund – Police.

The content of this article represents the views of the author and is his/her sole responsibility. The European Commission does not accept any responsibility for use that may be made of the information it contains.

References

| ↑1 | European Parliament resolution of 19 September 2019 on the importance of European remembrance for the future of Europe (19/07/2019). European Parliament. Available at: https://bit.ly/2TwajhG |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Goodenough, P. (2020). Turkey’s Erdogan Seeks to Link Antifa in US With US-Allied Syrian Kurdish Fighters. CNS News. Available at: https://bit.ly/2HISJUF |

| ↑3 | See Resonant Voices Radar for a more in-depth analysis |

| ↑4 | Defend History: Declaration. (2020). Udruženje Krokodil. Available at: https://bit.ly/2HEeo0E |

| ↑5 | Deklaraciju o Zajedničkom Jeziku. (2017). Udruženje Krokodil (et al). Available at: https://bit.ly/34wv2rR |