Serbian taxpayers are unwittingly paying for an army of bots to promote the country’s ruling party and denigrate its rivals.

By Andjela Milivojevic

His Twitter name is ‘Robin Xud’, a Serbian homage to the legendary English outlaw hero who robbed from the rich and gave to the poor.

And just like the Sheriff of Nottingham in the ballads of Robin Hood, Xud’s enemy resides in a castle, in this case an Internet database registered in 2017 at www.castle.rs.

Staring into two monitors in a dimly-lit room, Xud – who spoke on condition BIRN did not reveal his true identity – is part of a small team of programmers tracking the online operations of Serbia’s ruling Serbian Progressive Party, SNS.

According to Xud’s band of merry men and the findings of a BIRN investigation, the Progressives run an army of bots via the ‘Castle’ working to manipulate public opinion in the former Yugoslav republic, where President Aleksandar Vucic, leader of the party, has consolidated power to a degree not seen since the dark days Slobodan Milosevic at the close of the 20th century.

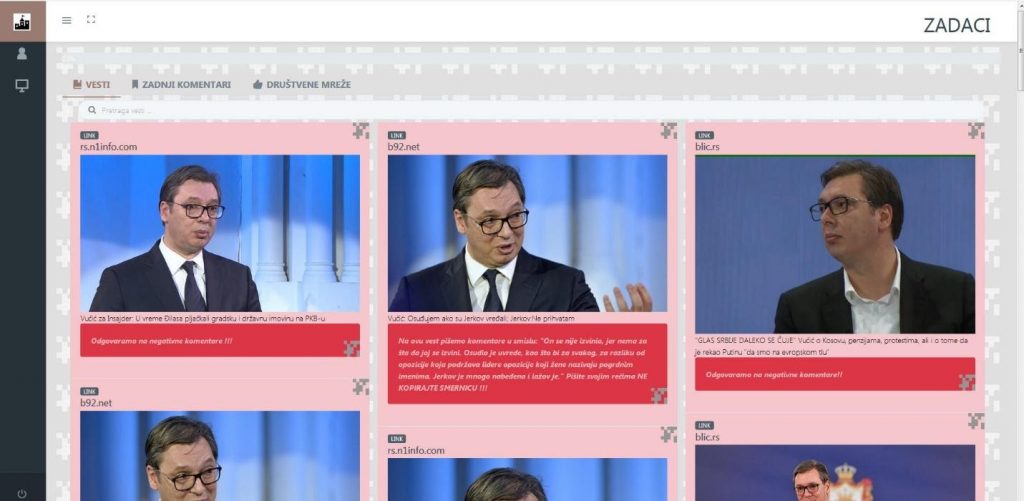

With the help of the programmers, this reporter gained exclusive access to the network for several months in 2019, observing how hundreds of people across Serbia log into the Castle everyday during normal working hours to promote Progressive Party propaganda and disparage opponents, in violation of rules laid down by social network giants like Twitter and Facebook to avoid the coordinated manipulation of opinion.

It is a costly operation, one that the Progressive Party has not reported to Serbia’s Anti-Corruption Agency. But the party doesn’t foot the bill alone.

This investigation reveals that some of those logging into the Castle are employees of state-owned companies, local authorities and even schools, meaning their botting during working hours is ultimately paid for by the Serbian taxpayer.

“Right now, over 1,500 people at least are botting every day,” said Xud. “They sit there in their jobs and instead of working they spit on their people.”

‘This is not activism’

The Progressive Party took power in Serbia in 2012, four years after Vucic split from the ultranationalist Serbian Radical Party and declared himself a changed man who now favours integration with the European Union after years of demonising the West.

As the opposition splintered, the Progressive Party established itself as the dominant political force with Vucic as its strongman. It is widely expected to win handsomely in parliamentary elections on June 21.

Serbia’s minister of information during the 1998-99 Kosovo war, when NATO bombed to halt a wave of ethnic cleansing and mass killing in Serbia’s then southern province, Vucic has presided over a steady decline in media freedom since taking power.

Critics find themselves shouted down and pushed to the margins, the most vocal dissenters often targeted for online abuse.

In April this year, the Progressive Party’s online escapades made international headlines when Twitter announced it had taken down 8,558 accounts engaging in “inauthentic coordinated activity” to “promote Serbia’s ruling party and its leader.”

BIRN has reported previously on how some of these accounts made their way into pro-government media, their tweets embedded in articles as the ‘voice of the people’.

This story lifts the lid on the scope of the Progressive Party’s campaign, how it directs the tweets, retweets and ‘likes’ of an army of people and how ordinary Serbs are footing part of the bill.

“This is not about activism, where a person writes what he wants or what he believes in,” said Xud. “These people have tasks; it is literally written what they need to criticise and how to criticise”.

The Progressive Party did not respond to questions submitted by BIRN for this story. However, in early April, after the Twitter announcement, Slavisa Micanovic, a member of the party’s main and executive boards, took to the platform to dismiss claims about a “secret Internet team” within the party, saying everything was public and legitimate.

“What exists is the Council for Internet and Social Networks, established in the party congress of 2012 and which can be found in the Statute and deals with promoting the party on the Internet and social networks,” Micanovic tweeted.

Reporting for duty

One August day in 2019 began like this:

At 7.56 a.m., a user named Nada Jankovic logged into the Castle from the town of Negotin, near Serbia’s eastern border with EU members Romania and Bulgaria. “Good morning, duty officer,” Jankovic wrote. Minutes later, in Sabac, just west of Belgrade, Dusan Ilic joined in with the words, “Good morning all”.

The bots had reported for duty, each entering the Castle system via a private account.

Xud and his team first accessed the Castle in January 2019 via an account with a weak password.

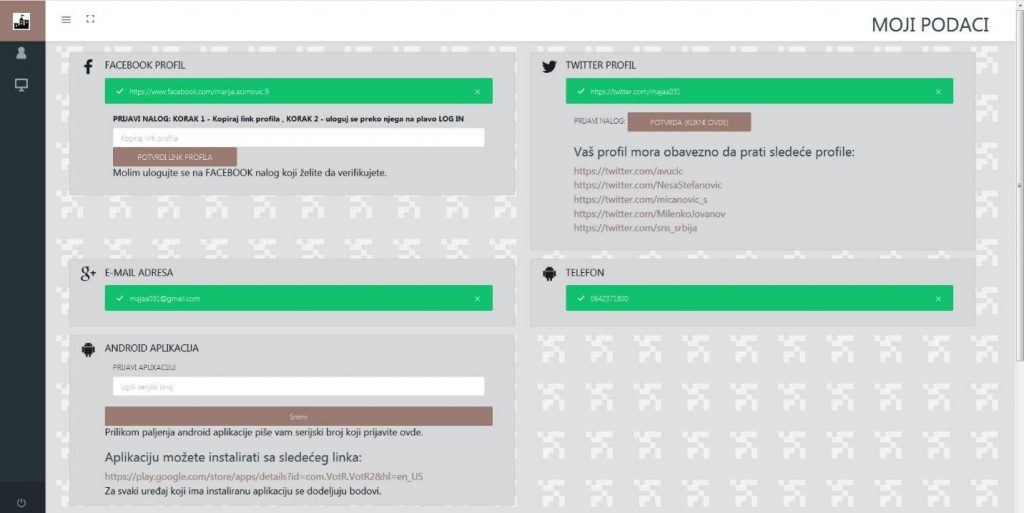

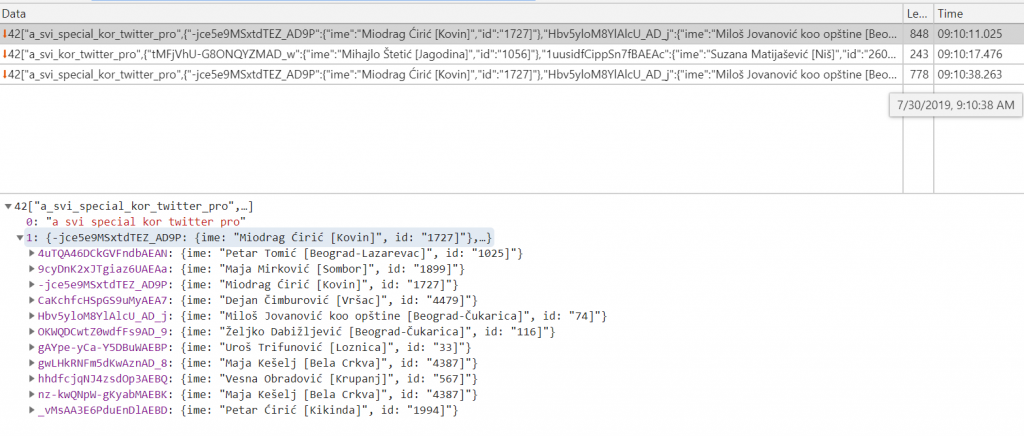

The Castle, they found, links to all Facebook and Twitter accounts operated by each user – frequently more than one per user – and lists five Twitter profiles they are obliged to follow: the official accounts of the ruling Progressive Party, President Vucic and Interior minister Nebojsa Stefanovic, as well as the accounts of two Progressive Party officials – deputy leader Milenko Jovanova and Micanovic.

‘Daily performance reports’ contain the name of the user, the municipality where they logged in and the extent of their activity on a given day: comments, likes, retweets and shares.

Points are allocated depending on how busy a user has been, though it is not clear whether this translates in rewards.

“The system is designed to follow every step the bot takes, from morning to night,” said Xud. “Everything is recorded in the Castle.”

Once logged on, the bots await their instructions.

On August 2, it was to shoot down criticism of Vucic’s appearance the day before on a pro-government private television channel called Pink.

Vucic had caused a storm when he read from classified state intelligence documents the names of judges and intelligence officials who he alleged had approved covert surveillance against him between 1995 and 2003, a period when Vucic, then a fierce ultranationalist, was in and out of government.

Critics accused him breaking the law by quoting from classified files.

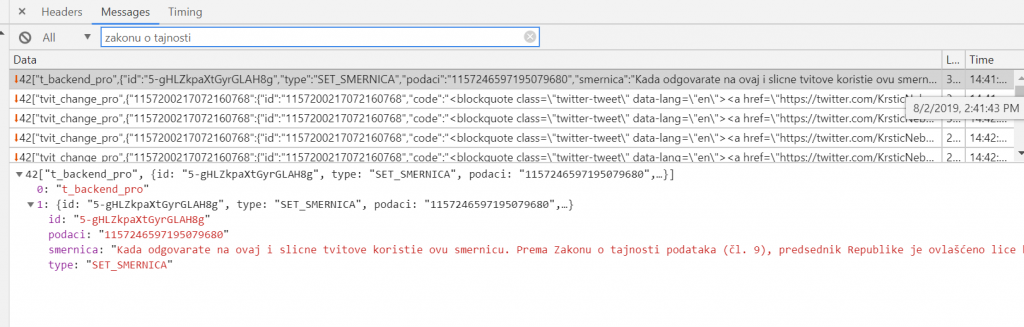

So the Castle kicked in, with the following instruction:

“When replying to this and similar tweets, use this guideline: According to the Law on Data Secrecy (Article 9), the President of the Republic has the authority to extend the secrecy deadline (Art. 20) and revoke the secrecy seal (Art. 26) if it is in the public interest.”

Days later, on August 5, a picture of Vucic started doing the rounds on Twitter in which he wore sneakers that critics said were worth 500 euros. The Castle turned its sights on his political opponents, Dragan Djilas and Vuk Jeremic; one bot tweeted, “Where did Djilas get half a million euros in his account from?”

In the space of just one day that BIRN monitored, the Castle bots were sent 60 different Twitter posts they were instructed to combat; the majority were posted by opposition leaders Djilas, Jeremic, Bosko Obradovic, Sergej Trifunovic, Dragan Sutanovac, Zoran Zivkovic and Velimir Ilic.

The Castle ‘special bots’ in charge of issuing instructions stressed the need to avoid detection; in late January 2019, users received a link to a statement by Vucic in which he condemned insults directed by his former mentor, the firebrand Radical Party leader Vojislav Seselj, at a female MP from the opposition Democratic Party, Aleksandra Jerkov.

The instruction read: “We are writing comments on this news in the sense: He (Vucic) did not apologise, because there is nothing to apologise for. He condemned the insults as he would for anyone, unlike the opposition which supports opposition leaders who call women derogatory names.”

“Write in your own words,” it stressed. “DO NOT COPY THE GUIDELINE!!!”

Botting while at work, on the taxpayer dime

Among those receiving such guidelines is Milos Jovanovic, a public sector employee former in the youth office of the local authority in Cukarica, a municipality of the Serbian capital, Belgrade, but now deputy director of the Gerontology Centre in Belgrade, which helps care for the elderly.

Jovanovic is paid out of state coffers. But according to BIRN monitoring, last year he spent much of his working day logged into the Castle. He declined to comment when contacted by BIRN.

Fellow Castle users are Mirko Osadkovski, employed in the local authority in Zabalj, northern Serbia, as a member of the Commission for Statutory Issues and Normative Acts and a local councillor, and Damir Skrbic, a municipal accountant and local councillor in the municipality of Apatin near the western border with Croatia.

Osadkovski did not reply to emailed questions. Skrbic declined to comment when reached by phone.

But they are not the only ones.

The Castle database contains the names of at least two Progressive Party people elected to the local assemblies of Vrsac, near the Romanian border northeast from Belgrade, and Sabac – Milena Kopil and Nenad Plavic respectively.

Kopil responded that she would not comment for BIRN. “As someone who supports the policies of Aleksandar Vucic, I have absolutely nothing positive to say about BIRN,” Kopil said. Plavic said he would only talk after the June 21 election.

Then there are those employed in public enterprises such as state-owned power utility Elektroprivreda Srbije, and others who work in schools.

In August last year, the Nis-based portal Juzne vesti published the ‘testimony’ of an unnamed Progressive Party member and former member of the party’s ‘Internet team’ who said that the bots had been organised by party officials with the intention of creating a false image of public satisfaction with the government. He also said that most of the bots were employed in public companies and risked dismissal if they did not follow orders.

Costly operation

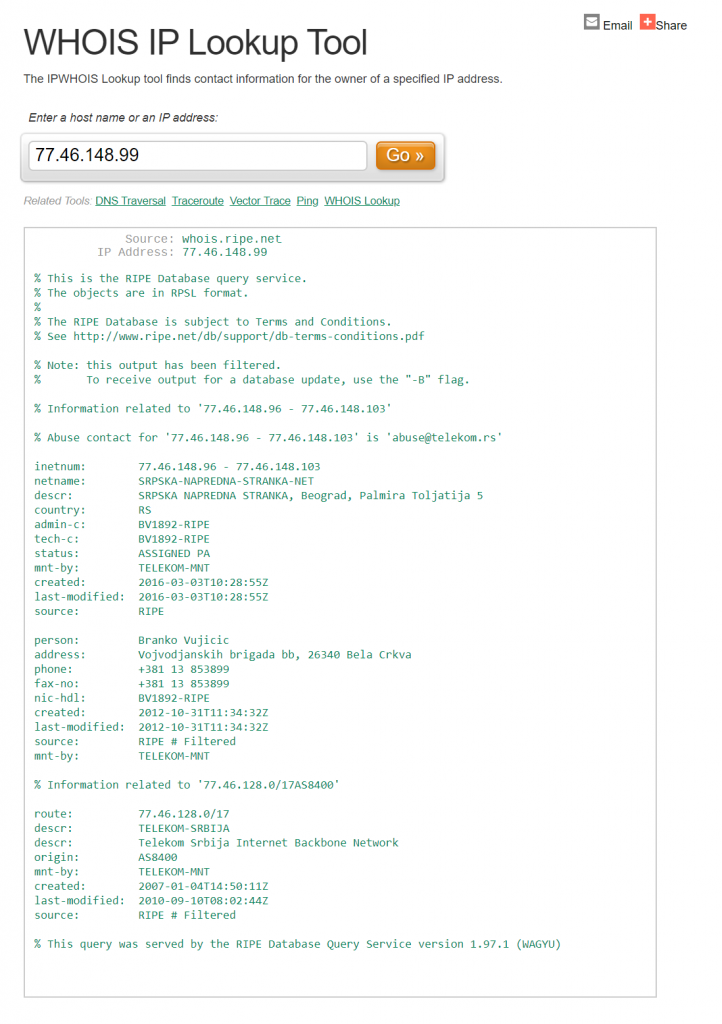

The website http://castle.rs/ was first registered in October 2017. Its ownership has not been visible since the privacy clause for this domain was activated. But there is ample evidence that it is controlled by the Progressive Party, not least the IP address.

According to the IPWHOIS Lookup tool on ultratools.com, the site’s IP address, 77.46.148.99, was registered in March 2016 at the same address as the party’s Belgrade headquarters in Palmira Toljatija Street. It is one of eight IP addresses leased by the party, from 77.46.148.96 to 77.46.148.103.

The ultimate owner is Telekom Srbija, a state-owned telecommunications company.

BIRN asked Telekom Srbija how much the Progressive Party pays for use of its static IP addresses and when the lease agreement was made. The company replied:

“Telekom Srbija has a commercial contract with the SNS, just as we have commercial contracts with thousands of other legal entities. We repeat, we cannot disclose the details of contracts with our customers.”

However, Andrej Petrovski, a cyber forensics specialist and Director of Tech at the Belgrade-based SHARE Foundation, which works to advance digital rights, said such an operation “does not come cheap.”

“Apart from renting a certain server or buying it and physically keeping and maintaining it – which is the more expensive operation – they also need to buy a domain, a certificate for protection of communication and fixed IP addresses,” Petrovski told BIRN.

“They need administrators who will administer the database and of course there is the cost of the people who work, who are managed through that application.”

Successive Serbian governments have used their hold on power to fill public sector bodies with party loyalists, and the Progressives are no different.

Petrovski said he doubted any other political party had the resources to mount a similar operation on such a scale.

“At the moment, I don’t think any other political party has the money to invest in something like this or is big enough to have an efficient system,” he said. “SNS is proud to have the most activists and to be the largest party in Serbia. It’s logical they are the only ones with the resources and the need for such a tool.”

Hidden costs

Political financing laws in Serbia require parties to report their expenses to the Anti-Corruption Agency, which is tasked with preventing financing abuses.

But the Progressive Party’s financial reports since 2013 make no explicit mention of the money spent to create and maintain the Castle system.

“In itself, it is not against the law on financing political activities for a party to buy such software or pay activists to work on it, but it must be recorded in the financial reports,” said Nemanja Nenadic, programme director at the Serbian chapter of Transparency International.

“If it is not recorded financially, then that is a problem.”

“If it was paid for by someone other than the party itself, then it should have been reported as a gift, as a contribution given to the political party by the person who made the payment,” Nenadic told BIRN.

BIRN asked the Anti-Corruption Agency whether the Progressive Party had ever reported such costs. In its response, the Agency cited all obligations a political entity has in terms of reporting its holdings and expenses, but did not comment on the specific case.

Mladen Jovanovic, head of the National Coalition for Decentralisation, which promotes civic participation in local politics, said there was a simple explanation for how some of those working on Castle are paid: from state coffers via public sector jobs.

“The flow of money needs to be checked,” said Jovanovic, whose coalition follows the misuse of public money in Serbia. “That’s the task of the prosecution, because we’re talking about corrupt work that damages the budget.”

“That old dream of all totalitarian regimes, that all citizens say what the leader thinks, has been realised in virtual time by creating in essence virtual citizens.”

On the receiving end

Like any other political party, the Progressive Party does not deny promoting itself on social media, but says its ‘Internet team’ is made up of party activists no different from those canvassing for support on the streets.

But BIRN’s analysis of the Castle database shows that the bots do not stop at promoting the party; they frequently target public figures, including journalists and NGO activists.

Zoran Gavrilovic, a researcher for the think-tank Bureau for Social Research, BIRODI, experienced this first hand after he appeared on television to discuss his findings with regards the ruling party’s dominance of the media landscape in Serbia.

Facing a string of insults and threats via Twitter, Gavrilovic responded with the tweet: “A bot is a person who, of free will or due to blackmail, abuses the right to free speech in online and offline space. Botting is a corrupt form of behaviour directed against the public, governance, freedom of speech and the rights of citizens.”

Speaking to BIRN, Gavrilovic said lawmakers should act to rein in such behaviour.

“I look at it as like the para-military formations of the 1990s [during the Yugoslav wars]. There’s no public debate. You are simply an enemy who should be spat on and kicked immediately. It is a para-political organisation.”

The Castle, however, is not the Progressive Party’s first attempt at manipulating public opinion in Serbia via social media.

In 2014, Xud and his fellow programmers uncovered an application called ‘Valter’, after the popular 1972 Yugoslav film about Partisan resistance fighters, Walter Defends Sarajevo.

Unlike the Castle, which works via the Internet, Valter was installed on the home computers of activists and members of the Progressive Party’s Internet team.

Valter was eventually replaced by Fortress, but when the Serbian portal Teleprompter reported on its existence in April 2015 hackers managed to take down the text and eventually the entire site, which no longer exists. Teleprompter no longer exists.

While the Progressive Party did not respond to a request for comment on this story, Vucic did hit back when Twitter took down the almost 9,000 accounts it accused of “inauthentic coordinated activity” to promote him and his party.

“I’ve no idea what it’s all about, nor does it interest me,” he told a news conference on April 2. “I’ve never heard that anyone on Twitter ever had anything positive to say about me.”

Such denials ring hollow for people like Xud. “People have to know that something like this exists,” he said.

Andjela Milivojevic is a Serbian investigative journalist, specialising in reporting about corruption and crime. For nearly ten years, she worked for the Centre for investigative journalism of Serbia and is now a freelance reporter for several media outlets in Serbia and Kosovo.

This article has been produced as part of the Resonant Voices Initiative in the EU, funded by the European Union’s Internal Security Fund – Police.

The content of this story represents the views of the author and is the sole responsibility of BIRN. The European Commission does not accept any responsibility for use that may be made of the information it contains.